Mannerist and Baroque Style: Divided and Multiple Selves

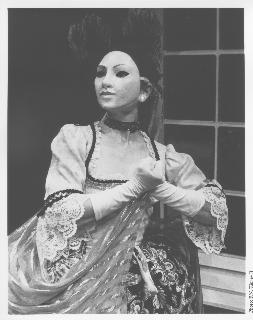

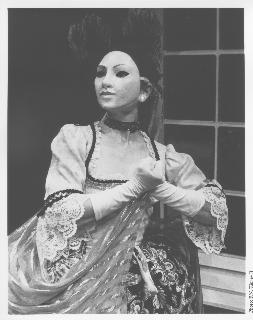

Baroque Dancer Catherine Turocy in Mask

French court dance styles became popular in England when Charles II's Restoration (1660) brought the exiled English court back from the Continent. Even before this time, however, the stresses of England's cultural slippage into Modern modes of thought had brought into poetic fashion first the so-called "Mannerist" style we see in Donne and Herbert, violently shaping and reshaping both the form and content poems' initial conceits until readers are brought to see them from exotic perspectives (the Universe contracted to a reflection in the Beloved's eye, two souls mingled to perfection outlasting the rest of Creation, a tenant-landlord negotiation that saves the poet's soul, a shattering series of outrageously worded demands or denials turned into acceptance by a simple request in ordinary diction). Milton, in poetry, and Bach, in music, reacted to these marvelous distortions by attempting to contain them, and all other possible variations of point of view, in Baroque compositions that frequently developed in "fugue" or dialogic structures, such as Paradise Lost's shifting between Hell and Heaven and Earth in alternating books. The ultimate expression of the C17 shattering of any pretense of a monadic (unified/singular) identity is the wearing of masks, first on stage and at court, then in the London streets, as women (and some men) took refuge behind literal "personae" as they negotiated the complexities of selves divided by being able to see from multiple points of view, none of which they could completely affirm or deny. Satan now had as persuasive a voice as God once did, and Parliament's reasons for killing the king were as reasonable as those for bringing him back from Paris. Go figure. Here we are.