The "Megaron" or "Great Hall" and Mycenaean Culture (ca. 1600-1550 B.C.E.)

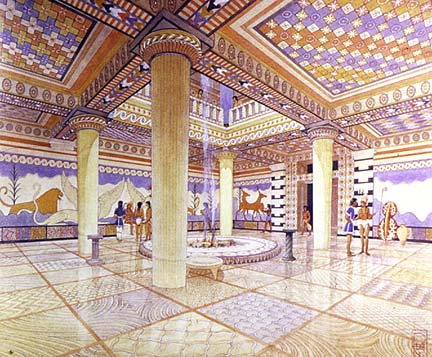

Unlike the city-states of the later, "Classical" Greek era, Mycenaean culture was rigorously hierarchical, with power controlled by dynastic kings and exercised by their warrior elite. Mycenaean kings collected taxes in the form of food and crafts from the surrounding farmers and craftspeople they protected, and who occasionally raided other sites to acquire concentrated wealth in the form of refined metals (gold, bronze, tin) and slaves. Homer's tale of the battle for Troy could be seen as an especially large raid of this type, as could the various stops for plunder recorded during the narrative of Odysseus' return. In this artist's reconstruction based on the archeological excavations at "Nestor's Palace" above Pylos, the throne stands against the back wall, facing a fire-pit that is open to the sky. Kings exercised priestly functions by routinely sacrificing wine, grain, and meat to the gods. The four columns which support the roof and the circular altar can be inferred by the survival of round footers and the raised fire pit in the floor at the archeological site.

Entrances on each side of the throne allow an orderly procession of petitioners and advisors to approach. Almost no defensive architecture is apparent in the foundation layout of the palace at Pylos, perhaps the reason why it was destroyed so rapidly by fire. All the Mycenaen fortresses were destroyed within a few decades of each other near the end of the thirteenth century B.C.E. Though the megaron above Pylos was in highlands above the harbor, the approach was relatively easy and not guarded by walls or other fortifications. The invaders who destroyed it and burned what they could not carry off left behind rows of vessels to hold grain and wine in the storehouses beside the megaron and many fire-hardened clay tablets in the "Linear B" Greek script, a hybrid pictographic and iconographic writing system contemporary with Homer's compositions. Though a thriving oral "literature" co-existed with this script, to date scholars have found it used only to record tax receipts.

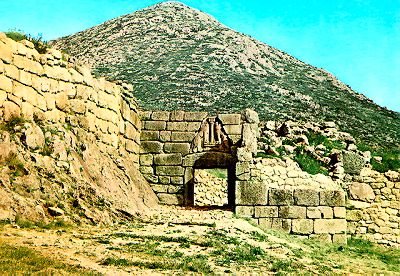

The megaron on the akropolis Mycenae, behind the coastal city of Argos, was the site archeologist Heinrich Schleimann used to name the entire culture. Its architecture is more typical of the highly fortified defenses found elsewhere at Thebes, Tyrins, and Athens.

This image above is Mycenae's megaron. seem from behind the throne and looking toward the fire pit and its four supporting-column footers. The site is at the edge of the mountains about five miles from the seaside port of Argos, the city myth tells us was ruled by Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. This was the fortress of their akropolis, the well-defended "high-city" to which the coastal dwellers could flee to escape water-borne invasions. As you will see, attack from the land side would have been very difficult. On the far side of the throne room, the wall stands at the top of a steep precipice hundreds of feet above the plain below. The megaron is the rectangular structure seen below on the upper right side of this aerial view, and the dark valley below stretches out to the coastal plain and Argos by the sea.

The palace sits on a plateau commanding the plains below with a clear view of any approaching travelers from the sea, much less a force of military size. The blue above the tomb-circle walls in the image below is the Argolic Gulf, which ends in the modern city of Nauplion and the modern city and ancient ruins of Argos.

The approaches to the megaron are protected by a high, thick parallel wall that leads up to the "Lions Gate." Although such lion decorations also are found on entrance gates in Asia Minor, in this location the twin lions may perhaps also be associated with the claims of mythic ancestry descending from Agamemnon and Menalaos, the brother-kings of Argos and Sparta.

The walls are so thick that, unseen from this view, a guard chamber or shrine has been let into the side of the opening immediately beneath the lions. Metal-reinforced wooden gates would have spanned the opening and protected the guards from approaching travelers, who would have to walk many yards unprotected beneath defenders on the corridor walls. Inside the gate, the path winds through a circular-walled cemetery containing numerous shaft tombs from which Schleimann recovered golden masks and chains, and bronze-age weapons. That is the circle of stone near the bottom of the aerial view above.

In effect, the spirits of the dead kings and their warriors form the first inner defense of the fortress, between the gates and the megaron. The photo above shows the surviving stones of a double-walled sentry path that completely surrounds the precincts of the dead.

In the center of the akropolis, a tunnel cut deep into the rock leads down to a spring from which the fortress could be supplied with water during sieges.

Above and behind the palace on its plateau, a tall peak provides the ideal vantage point from which approaching ships in the Argolic Gulf could be seen before they touch the beach far below. This would also have been an ideal position to locate a watchman for distant beacon fires located on other similarly tall peaks between Argos and Troy, such as that imagined in the Watchman's speech in the opening scene of Aeschylus' Agamemnon.