Homer, The Odyssey, Books 22, 23, 24

Athena increasingly enters the plot of the epic in the later books, and

finally in Book 22, she appears to the Suitors in her own form, wielding the

shield of Zeus. The Aegis bears the Gorgon's head, won by Perseus in

battle, and it strikes terror in the hearts of all who see it. This is

Athena Nike or Athena Victorious, the battlefield manifestation of this

goddess of strategy, weaving, and guile.

Click here to see the famous

sculpture of Athena Nike known as the "Winged Victory of Samothrace."

If we continue to explore the Odyssey's use of the gods in an

Euhemeristic fashion, as representatives of abstract qualities and natural

forces, what might Athena's increasingly vivid presence mean for these

books?

The later books of the Odyssey also suddenly introduce us to the

narrative forms commonly found in the Iliad but rarely found in the

narrative of Odysseus' wanderings and homecoming. Most distinctive of

these are the death scenes of the suitors, which begin with clinically

precise descriptions of the death wound, the body's convulsive responses to

it, and the fall of the body to earth, usually with vivid auditory or visual

effects. In these late books, those images often are oddly ironic, as

when Antinous and Eurymakhos die with their blood defiling the food which

ought to have fed their blood. The maids' "dancing feet" also echo the

imagined dancing with the Suitors in their days of happy betrayal of

Penelope and Telemakhos.

A major part of this narrative

section's power is its rendering of archery in warfare. This is an

unusual feature of the Odyssey which will surprise readers of the

Iliad. According to later sources, Paris, Helen's cowardly

husband, uses a bow to kill Achilles, but its stand-off-and-kill technique

gives the warrior what might be considered an unfair advantage over even the

spear or javalin caster. In this situation, however, the unfair

advantage is more than compensated for by the suitors' numbers vs. Odysseus'

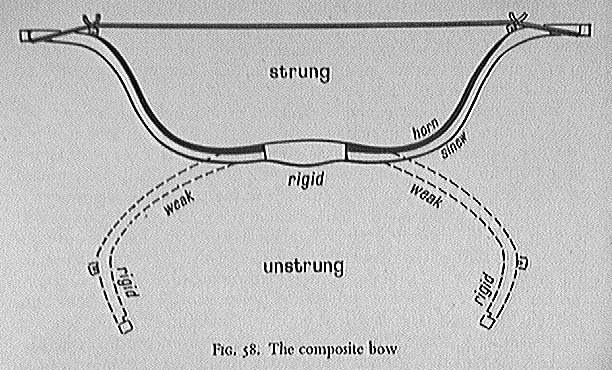

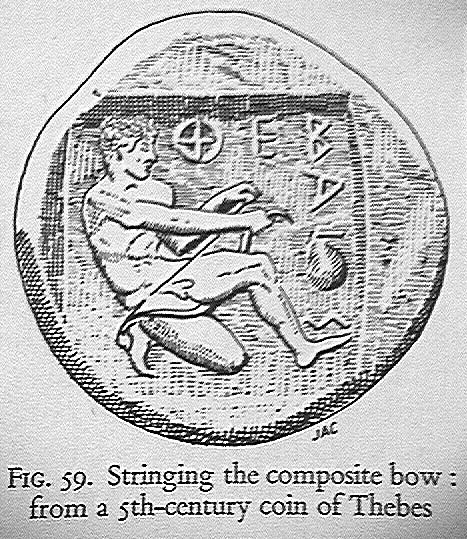

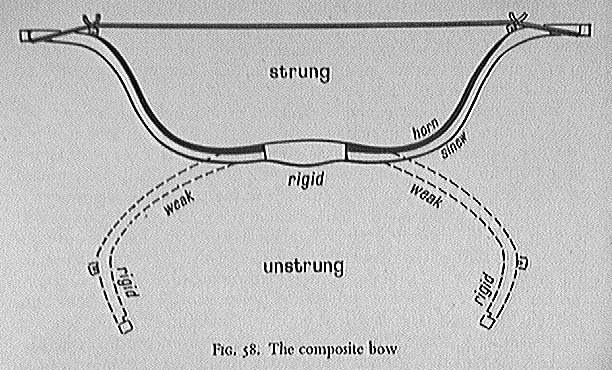

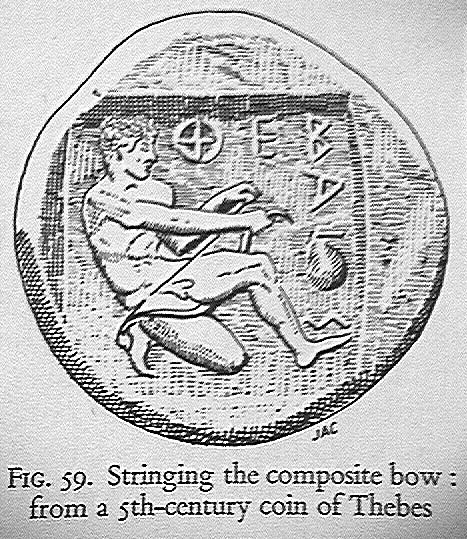

tiny war-band. Everything the poet

says Odysseus does with the bow is entirely plausible, and more astonishing

feats are possible. But first you have to string the bow.

Book 22--

1)

Note the order in which the suitors are killed.

How do the images associated with Antinoos' death summon up the poem's

previous thematic characterizations of the suitors' behavior?

Note the poet's sudden shift to Antinoos' perspective.

Why join the victim's point of view?

Also compare Eurymakhos' death.

2)

Once Odysseus has announced himself (compare with Clytemnestra to the

Chorus in Agamemnon), who is the first suitor to respond, why, and how

does he characterize the situation?

3)

What role does Melanthios play in the battle, and how would you

characterize it?

4)

How does Athena first intervene in the battle, and what does she do for

Odysseus (and for the reader) to put this battle in context?

5)

Note the extended simile in which Odysseus and his allies are described

as the suitors flee Athena's aegis (22: 337-346).

How does this relate to the poem's pattern of prophecy?

6)

When Agelaos, the seer, pleads for mercy, he charges that there is a

divine sanction for sparing him.

How would you explain it, and why doesn't Odysseus accept this as an adequate

reason?

7)

Who is saved in the hall, and why?

8)

With what extended simile are the suitors described as they lay dying in

Odysseus' hall? Where have we seen

a similar simile (or metaphor) used to describe this same type of scene?

9)

How do you explain the differences between the deaths of the

suitors and the deaths of the maids and the goatherd, Melanthios?

Book 23--

1)

How did Penelope react to Eurikleia's announcement of Odysseus' return

and the deaths of the suitors? Note

the patterns of formulaic language in the nurse's speech.

Also note Penelope's second response when she has been convinced.

2)

What are the customs of a Homeric-era town when a killing has occurred,

and how does Odysseus' plan to thwart these customs?

Note Phemios' role in this plan and its relationship to the "iron

wedding" theme.

3)

What is the key feature of Odysseus' bedroom, and why is this appropriate

for him?

4)

How does Penelope interpret Helen's behavior, and how might it shed light

on her behavior in Books 4 & 15?

5)

Once again we see the image of a swimmer in this narrative.

How is this used and how does it resonate with other

instances of swimmers saved?

(pp. 436-7, ll. 259-70)

6)

How does the narrator's summary recapitulation of Odysseus'

tale of his wanderings (told to Penelope) match your own memory

of the key events in the tale?

What is left out? What is

different about its narrative order?

What is its function at this

site?

7)

Apart from his expiation of the debt to Poseidon, what are Odysseus'

plans for the future and how do they shape your understanding of "business as

usual" in Ithaka?

Book 24--

1)

The suitors' arrival in the Underworld creates a loop to Book 11 and

introduces information about the lives and deaths of Achilles and Agamemnon.

What are they concerned about, and what do their deaths have to do with

the suitors and this plot?

2)

How does Amphimedon's version of the suitors' deaths compare with the

version previously given? What does

he emphasize? Also, can you detect

an inconsistency in the text's rules for entry into the Underworld here?

3)

When Odysseus confronts Laertes, how does Laertes discover

the truth about his identity?

Why does Odysseus force himself to watch his father's suffering?

4)

Who is Dolios and why is he introduced in this circumstance?

Why does Odysseus respond as he does to Dolios' questions about Penelope?

5)

How do the suitors' fathers interpret their deaths?

6)

What values are contained in the closing scene?

Is this true "closure," or

could the story go on? If so, how

might the singer continue it

tomorrow night?