Interior text block:

In late 12th-century (1100s) Umbria, possibly Assisi, a single scribe working in a well-equipped scriptorium copied the first six parts of the missal in two columns per page on the first 278 of 285 goatskin parchment leaves, or 143 whole goat kid skin "bifolia" (two-leaves folded in the middle). The resulting pages measure 30 x 21 cm (11.4 x 8.3 inches), about the size of standard U.S. letter paper. The leaves were sewn together in 29 "quires" or gatherings, usually of five bifolia each, making a stack 9.6 cm (3.8 inches) thick. All of the quires were sewn, one at a time, probably attached to three heavier, ca. 1.5 cm wide leather binding straps that were drawn through slots carved into wooden boards that have not survived, and stopped with "trenails" (wooden pegs). The spine and about 1/3 of each board was then covered by some kind of glued leather that has not survived, either. It probably was only a 1/3 leather binding, leaving about 2/3 of each board exposed for the life of the book.

At some later point, perhaps in the twelfth century, a second scribe copied another Mass in single-column format on the front and back of blank leaf 279, perhaps after cutting away most of the preceding blank leaf to leave the "stub" (278bisr-278bisv). Somewhat later, but still in the thirteenth century, yet another hand used the remaining six blank leaves to write a monthly calendar of feast days on the front and back (recto and verso), one month per side.

Sometime in the fifteenth century (1400s), the old binding became too unstable to use because of steady daily wear as the Mass and other feasts' services were sung The boards also apparently had suffered damage because they were replaced at around the same time. Rebinding was performed, inexpertly, with sloppy, crooked resewing that left new stitching holes in the parchment quires' folds.

Exterior binding:

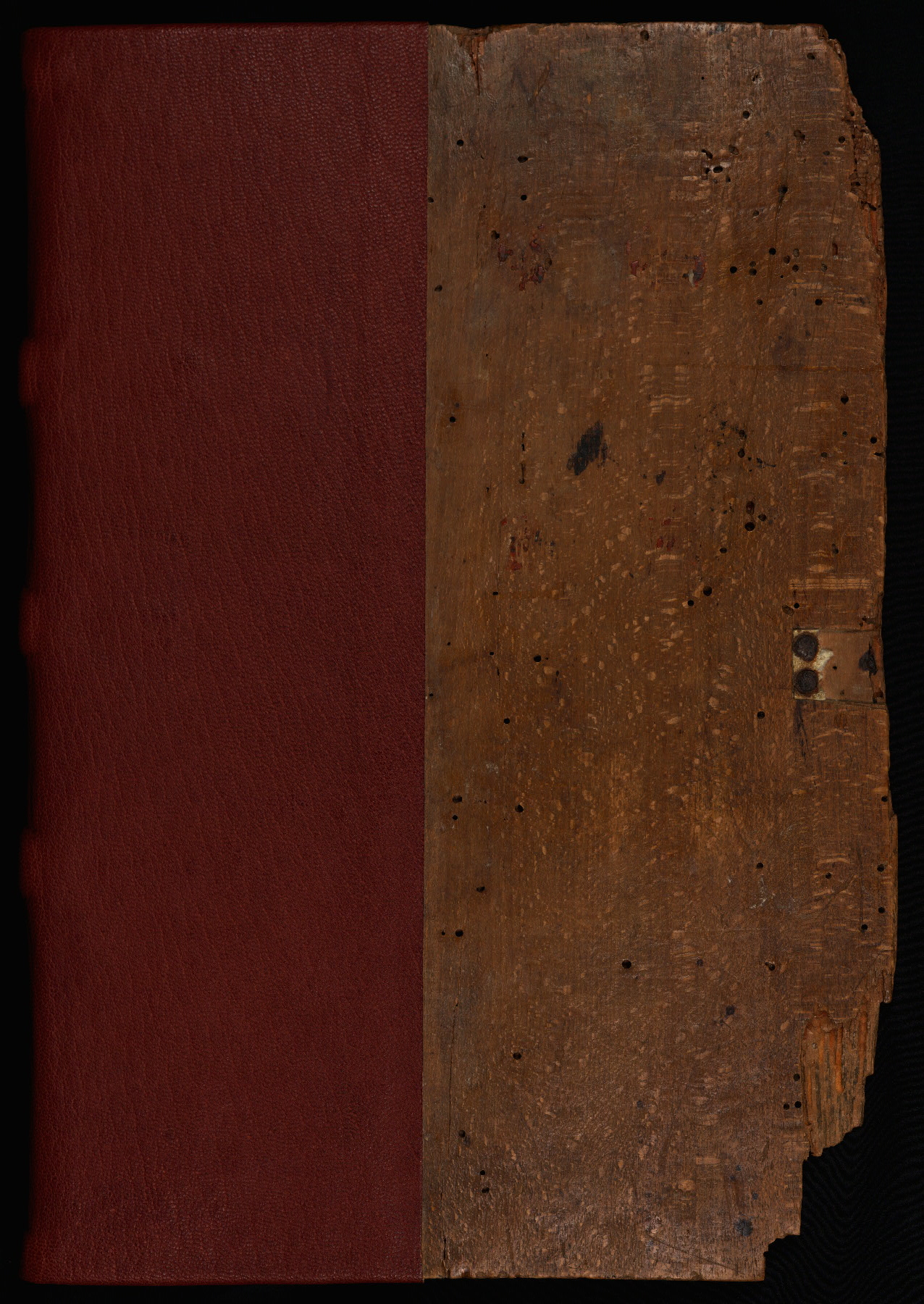

During the fouirteenth-century rebinding, two new beech boards were attached, each roughly the same size as the individual leaves. On their insides were "pastedowns" to protect the parchment leaves, each made from a bifolium of a smaller, eleventh-century (1000s) portable missal, the sheets turned sideways before being glued down. At that time, the text block was trimmed square at the top edge, probably to remove worn or torn edges, with some loss of marginal notes. The quires were resewn to attach them to three alum-tawed leather straps, once again drawn through the slots carved near the boards' edges and stopped by trenails to secure them. The new fourteenth-century leather 1/3 spine binding lasted until the nineteenth-century (1800s) when it was replaced by another, distinctly poor quality piece of leather which, by the mid-1800s, had already begun to crack where each board joined the spine.

Probably very early in the missal's life, insects had attacked the beech wood boards to lay their eggs in burrows, suggesting the book was left out in the open with the boards exposed, perhaps on the Church of San Nicolo altar, rather than covered with protective cloth and stored in a closed book chest or cupboard. The insect damage penetrated not only the boards but also the eleventh-century missal pastedowns on their interiors and the first and last leaves of W.75, itself. By the mid-1800s, the boards had started to flex when opened. When the church of San Nicolo was damaged by an earthquake in the early nineteenth century, and deconsecrated, its relics and apparatus would have been dispersed. We do not know how the missal, described as a "breviary," came to be in the catalog of Frankfort bookseller Joseph Baer & Co. for 1905, 1911, and 1924, but around 1924 the manuscript was acquired by Henry Walters' Paris agent, Paul Gruel, who sold it to him in that same year.

In 2016, Mellon Fellow Cathie Magee, under supervision of Walters Head Conservator Abigail Quandt, analyzed, disbound, and repaired the book, filling holes in the boards using modern synthetic gels and other reversible materials. She then resewed all the disbound quires, reattached them to new straps, and bound them to the old boards. The spine was covered with a new 1/3 binding in goatskin from Pergamena Parchment (Jessie and Stephen Meyer, Montgomery NY).

The Walters has not published the images recording the conservation process of W.75, but a very similar but smaller manuscript's conservation disbinding is recorded by online imagesadapted from an online 2011 Book History module written by Dr Nicola Royan and Dr Joanna Martin of the School of English Studies at The University of Nottingham. Click here to see the disbinding examples, which begin roughly one full leaf scroll down from the top of the page. Click here to follow the whole series from Materials through Inks, Illumination etc.

Binding as Evidence of Use:

W.75 was bound for long-term, very frequent use, and survived that heavy use for over five hundred years. Its original binding apparently was worn out and removed after its first two hundred years of service, but the parchment text block remained bright and almost entirely legible at least until that period. In the second binding's four hundred years of life, the book must have continued to be exposed to the insects which were slowly devouring the beech wood boards while raising their young. This would be consistent with a missal's presence on the altar where it would be consulted, or at least raised in benediction, by the priest celebrating the Mass several times each day, every day of the year. The book was almost certainly never "read" from cover to cover, or even in significant sections. It was intended as a memory aid to guide celebrants through the Church's daily, weekly, monthly, and annual dramatic celebration of the congregation's relationship with God. Because priests were expected to know their parts by memory, the texts of Bible passages often were extremely abbreviated. The earliest version of "The Legend of the Three Companions," called "Anonymous of Perugia," says that none of the three read Latin well enough to understand what the parish priest was pointing at, so the difficulty for laymen trying to read the missal's abbreviated Latin conforms to the legend's version of events (Augustine Thompson, Francis of Assisi, 23). The book's probable presence, readily accessible on the altar, and quite probably the only large sacred book in such a small parish church, also improves the case for its identification as the book used in the Bible oracle. At some point fairly early in its life, a second scribe added the short Mass for the Holy Sacrament (ff. 279r-279v) and a second scribe, probably in the thirteenth century, added the calendar on the last six leaves. These adaptations kept the missal in use as new saints were added over the centuries, including Clare of Assisi and Francis, himself, an addition which dates the corrected calendar to after Francis's 1228 canonization.

Photo of Cathie Magee working on back board: Amy Davis, Baltimore Sun

Image of repaired front board from The Digital Walters

Image of repaired W.75 open to

the Crucifixion illumination that begins the Canon of the Mass, ff.

166v-167r, the Cross forming the "T" of "Te igitur clementissime Pater

[Thee, therefore, most merciful Father], by Amy Davis, Baltimore Sun