From Master of the Crossroads

Pantheon Books, 2000

Copyright 2000 by Madison Smartt Bell

All Print Rights Reserved

Order Master of the Crossroads Online

A version of this chapter appeared in Granta #54, 1996,

under the title "Waiting for the General"

1

Midday, and the sun thrummed from the height of its arc, so that the lizard seemed to cast no shadow. Rather the shadow lay directly beneath it, squarely between its four crooked legs. The lizard was a speckled brown across its back but the new tail it was growing from the stump of the old was darker, steely blue. It moved at a right angle and turned its head to the left and froze, the movement itself as quick and undetectable as a water spider's translation of place. A loose fold of skin at its throat inflated and relaxed. It turned to the left and skittered a few inches forward and came to that same frozen stop. When it turned its head away to the right, the man's left hand shot out like a whiplash and seized the lizard fully around the body. With almost the same movement he was stroking the lizard's underbelly down the length of the long broad-bladed cutlass he held in his other hand.

The knife was eighteen inches long, blue-black, with a flat spoon-shaped turning at the tip; its filed age was brighter, steely, but stained now with lizard blood. The man hooked out the entrails with his thumb and sucked moisture from the lizard's body cavity. He cracked the ribs apart from the spine to open it further and splayed the lizard on a rock to dry. Then he cautiously licked the edge of his knife and sat back and laid the blade across his folded knees.

At his back was the trunk of a small twisted tree, which bore instead of leaves large club-shaped cactile forms bristling with spines. The man contracted himself within the meager ellipse of shade the tree threw on the dry ground. Sweat ran down his cheeks and pooled in his collarbones and overflowed onto his chest, and his shrunken belly lifted slightly with his breathing and from time to time he blinked an eye, but he was more still than the lizard had been; he had proved that. After a time he looped his left hand around the lizard's dead legs and picked up the knife in his other hand and began to walk again.

The man was barefoot and wore no clothes except for a strip of grubby cloth bound around his loins; he had no hat and carried nothing but the cane knife and the lizard. His hair was close-cut and shaved in diamond patterns with a razor and his skin was a deep sweat-glossy black, except for the scar lines, which were stony pale. There were straight parallel slash marks on his right shoulder and the right side of his neck and his right jawbone and cheek, and the lobe of his right ear had been cut clean away. On his right forearm and the back of his hand was a series of similar parallel scars that would have matched those on his neck and shoulder if, perhaps, he had raised his hand to wipe sweat from his face, but he did not raise his hand. Along his ribcage and penetrating the muscle of his back the scars were ragged and anarchic. These wounds had healed in greyish lumps of flesh that interrupted the flow of his musculature like snags in the current of a stream.

He was walking north. The knife, swinging lightly with his step, reached a little past the joint of his knee. The country was in low rolling mounds like billows of the sea, dry earth studded with jagged chunks of stone. There were spiny trees like the one where he'd sheltered at midday, but nothing else grew there. He walked along a road of sorts, or track, marked with the ruts of wagon wheels molded in dry mud, sometimes the fossilized prints of mules or oxen. Sometimes the road was scored across by shallow gulleys, from flooding during the time of the rains. West of the road the land became more flat, a long dry savannah reaching toward a dull haze over the distant sea. In the late afternoon the mountains to the east turned blue with rain, but they were very far away and it would not rain here where the man was walking.

At evening he came to the bank of a small river whose water was brown with mud. He stood and looked at the flow of water, his throat pulsing. After a certain time he crept cautiously down the bank and lowered his lips to the water to drink. At the height of the bank above the river he sat down and began eating the lizard from the inside out, breaking the frail bones with his teeth and spitting pieces on the ground. He gnawed the half-desiccated flesh from the skin, then chewed the skin itself for its last nutriment. What remained in the end was a compact masticated pellet no larger than his thumb; he spat this over the bank into the river.

Dark had come down quickly while he ate. There was no moon but the sky was clear, stars needle-bright. He scooped out a hollow for his shoulder with the knife point and then another for his hip and lay down on his side and quickly slept. In dream, long voracious shadows lunged and thrust into his side, turning and striking him again. He woke with his fingers scrabbling frantically in the dirt, but the land was dry and presently he slept once more. Another time he dreamed that someone came and was standing over him, some weapon concealed behind his back. He stirred and his lips sucked in and out but he could not fully wake at first; when he did wake he shut his hand around the wooden handle of the knife and held it close for comfort. There was no one near, no one at all, but he lay with his eyes open and never knew he'd slept again until he woke, near dawn.

As daylight gathered he fidgeted along the riverbank, walking a hundred yards east of the road, then west, trying the water with a foot and then retreating. There was no bridge and he was ignorant of the ford, but the road began again across the river, beyond the flow of broad brown water. At last he began his crossing there, holding both arms high, the knife well clear of the stream, crooked above his head. His chest tightened as the water rose across his belly; when it reached his clavicle the current took him off his feet and he floundered, gasping, to the other bank. He could swim, a little, but it was awkward with the knife to carry in one hand. When he reached shore he climbed high on the bank and rested and then went down cautiously to scoop up water in his hands to drink. Then he continued on the road.

By midday he could see from the road some buildings of the town of Saint Marc though it was still miles ahead, and he saw ships riding their moorings in the harbor. He would not come nearer the town because of the white men there, the English. He left the road and went a long skirting way into the plain, looping toward the eastward mountains, over the same low mounds and trees as yesterday. The edge of his knife had dimmed from its wetting and he found a lump of smoothish stone and honed it till it shone again. Far from the road he saw some goats and one starveling long-horned cow, but he knew it was hopeless to catch them so he did not try. There was no water in this place.

When he thought he must have passed Saint Marc he bent his way toward the coast again. Presently he regained the road by walking along a mud dike through some rice paddies. People had returned to the old indigo works in this country and were planting rice in small carrés; some squares were ripe for harvest and some were green with fresh new shoots and some were being burned for a fresh planting. When he reached the road itself there were women spreading rice to dry and winnowing it on that hard surface. It was evening now and the women were cooking. One of them brought him water in a gourd and another offered him to eat; he stayed to sup on rice cooked in a stew with small brown peas, with the women and children and the men coming in from the paddies. Some naked children were splashing in a shallow ditch beside the road, and beyond was the rice paddy lakou, mudwattled cabins raised an inch or two above the damp on mud foundations.

He might have stayed the night with them, but he misliked those windowless mud houses, whose closeness reminded him of barracoons. Also, white men were not so far away. The French had said that slavery was finished, but the man had come to distrust all sayings of white people. He saw no whites or slavemasters now among these people of the rice paddies, but all the same he thanked them and took leave and went on walking into the twilight.

He was as always alone on the road as it grew dark. The stars appeared again and the road shone whitely before him to help light his way. Presently he came away from the rice country and now on either side of the road the land was hoed into small squares for planting peas, but no one worked those fields at night, and he saw no houses near, nor any man-made light.

In these lowlands the dark did little to abate the heat, and he kept sweating as he walked; the velvet darkness closed around him viscous as sea water, and the stars lowered around his head to glimmer like the phosphorescence he had seen when he was drowning in the sea. He seemed to feel his side was rent by multiple rows of bright white teeth, and he began running down the road, shouting hoarsely and flailing his knife. Also he was afraid of loup-garous or zombis or other wicked spirits which bokors might have loosed into the night.

In the morning he woke by the roadside with no memory of ever having stopped. The sun had beat down on him for half the morning and his tongue was swollen in his head. There was no water. He raised himself and began to walk again.

Now it was bad country either side of him, true desert full of lunatic cacti growing higher than his head. The mountain range away to the east was no nearer than it ever had been. He passed a little donkey standing by the road, whose hairy head was all a tangle of nopal burrs it must have been trying to eat. He would have helped the donkey if he could but when he approached it found the strength to shy away from him, braying sadly as it cantered away from the road. The man walked on. Soon he saw standing water in the flats among the cacti, but when he stooped to taste it, the water was too salt to drink. Presently he began to pass the skulls of cows and other donkeys that had died in this desert place. Somehow he kept on walking. Now there were new mountains ahead of him on the road but for a long time they seemed to come no nearer.

Toward the end of the afternoon he reached a crossroads and stopped there, not knowing how to turn. One fork of the road seemed to bend toward the coast and the other went ahead into the mountains. Attibon Legba, he said in his mind, vini moin.... But for some time the crossroads god did not appear and the man kept standing on the kalfou, fearing to sit lest his strength fail him to rise again.

After a time there was dust on the desert trail behind him and then a donkey coming at a trot. When it came near he saw it bore a woman, old but still slender and lithe. She rode sideways on the wooden saddle, her forward knee hooked around the wooden triangle in front. The burro was so small her other heel almost dragged the ground, as did the long slack straw macoutes that were hung to either side of the saddle. She wore a brown calico dress and a hat woven of palm fronds, all brim and no crown, like a huge flat tray reversed over her head.

She stopped her donkey when she reached the kalfou. The man asked her a question and she pointed with the foot-long stick she held in her right hand and told him that the left fork of the road led to the town of Gonaives. She aimed the stick along the righthand fork and said that in the mountains that way there were soldiers-- black soldiers, she told him then, without his having asked the question.

She was toothless and her mouth had shrunken over the gums but still he understood her well enough. Her eyes combed over the scars on his neck and shoulder with a look of comprehension but at the old wounds on his side her look arrested and she pointed with the stick.

Requin, the man said. Shark.

Requin? the woman repeated, and then she laughed. B'en ouais, requin.... She laughed some more and waved her stick at the dry expanses all around them. The man smiled back at her, saying nothing. She flicked the donkey's withers with her stick and they went trotting on the road to Gonaives.

Too late he thought of asking her for water... but then those straw panniers had looked slack and empty. Still he continued walking with fresh heart. These were dry hills he was now entering, mostly treeless, with shelves of bare rock jutting through the meager earth. The road narrowed, reducing to a trail winding ever higher among the pleats of the dry mountains. At evening clouds converged from two directions and there was a thunderous cloudburst. The man found a place beneath a stone escarpment and filled his mouth and belly with clean run-off from the ledges and let the fresh rainwater wash him down entirely.

The rain continued for less than an hour and when it was finished the man walked on. Above and below the trail the earth on the slopes was torn by the rain as if by claws. By nightfall he had reached the height of the dry mountains and could look across to greener hills in the next range. In the valley between, a river went winding and on its shore was a little village-- prosperous, for land was fertile by the riverside. After the darkness was complete he could see fires down by the village and presently he heard drums and voices too, but the trail was too uncertain for him to make his way there in the dark, if he had wished to. It was cool at last, high in those hills, and he had drunk sufficiently. He scooped holes for his hip and shoulder as before and lay above the trail and slept.

Next morning there was cockcrow all up and down the mountains and he got up and walked with his mouth watering. The stream he'd seen the night before proved no worse than waist-deep over the wide gravel shoal where he chose to cross. Upstream some women of the village were washing clothes among the reeds. When he had crossed the stream he turned back and stooped and drank from it deeply and then began climbing the green hills with water gurgling in his stomach.

In a little time zig-zag plantings of corn appeared in rough-cut terraces rising toward the greener peaks. He broke from the trail and picked two ears of corn and went on his way pulling off the shucks and gnawing the half-ripened kernels, sucking their pale milk. After he had thrown away the cobs his stomach began to cramp. He hunched over slightly and kept on walking, pushing up and through the pain til it had ceased. Now there was real jungle above and below the trail, and plantings of banana trees, and mango trees with fruit not ripe enough to eat.

When he had crossed the backbone of this range, he began to see regular rows of coffee trees, the bean pods reddening for harvest. And not much further on were many women gathered by the trail's side, with goods arrayed for a sort of market: ripe mangos and bananas and soursops and green oranges and grapefruit. A woman held a stack of folded flat cassava bread and another was roasting ears of corn over a small brazier. Also a few men were there, and some in soldiers uniforms' of the Spanish army, though all of them were black.

The man crouched over his heels and waited, the knife on the ground near his right hand. The soldiers made their trades and left-- it was only they who seemed to deal in money. Among the others all was barter, but the man had nothing to exchange except his knife and that he would not give up. Still a woman came and gave him a ripe banana whose brown-flecked skin was plump to bursting, and another gave him a cassava bread without asking anything in return. Squatting over his heels he ate the whole banana and perhaps a quarter of the bread, eating slowly that his stomach might not cramp. When he had rested he stood up and followed the way the soldiers had taken, carrying his knife in one hand and the remains of the bread in the other.

The opening of the trail the soldiers used was hidden by an overhang of leaves but past this it widened and showed signs of constant use. The man crossed over a ridge of the mountain and looked down on terraces planted with more coffee trees. In the valley below was a sizeable plantation with carrés of sugar cane and the grand'case standing at the center as it would have done in the days of slavery not long since, but all round the big house and the cane fields was encamped an army of black soldiers.

He was not halfway down the hill before he tumbled over sentries posted there. They trained their guns on him at once and took away his knife and the remainder of his bread. They asked his business but did not give him time to answer. They made him put his hands up on his head and chivvied him down the terraces of coffee, prodding him with the points of their bayonets.

In the midst of the encampment some of the black soldiers glanced up to notice his arrival but most went on about their business as if unaware. The sentries urged him into the yard below the gallery of the grand'case. A white man in the uniform of a Spanish officer was passing and the sentries hailed him and saluted. The white man stopped and asked the other why he had come there. Despite the uniform his face was not of the Spanish cast and his accent was that of a Frenchman.

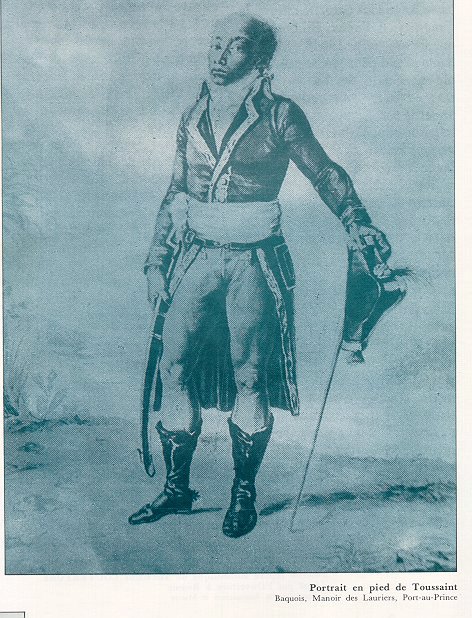

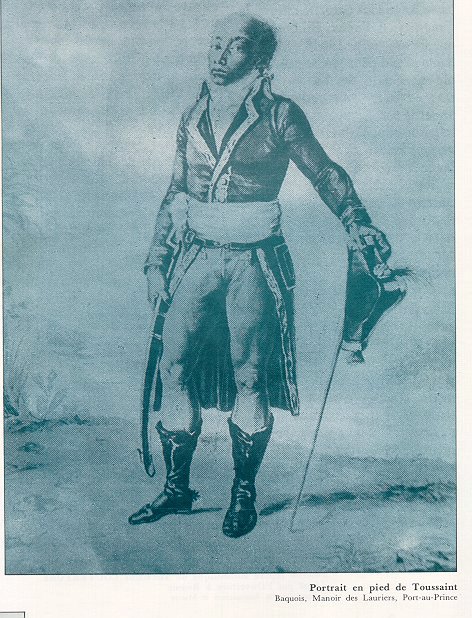

Where is Toussaint, the man said. Toussaint Louverture.

The white officer stared a moment and then turned and sharply saluted a black man, also in Spanish uniform, who was then approaching. The black officer turned and asked the man the same question once more and the man drew himself up and began to recite:

Brothers and Friends, I am Toussaint Louverture. My name is perhaps not unknown to you--

The black officer cut him off with a slashing movement of his hand and the man stared back at him, wondering if this could be the person he had sought (as the white officer had seemed to respect him so). But then a silence fell over the camp, like the quiet when birdsong ceases. A large white stallion walked into the yard and a black man in general's uniform pulled the horse up and dismounted. His face was no higher than the horse's shoulder when he stood on the ground, and his uniform was thoroughly coated with dust from wherever he'd been travelling.

The two junior officers saluted again and the black one drew near and spoke softly into the ear of the general. The general nodded and beckoned to the man who had walked into the camp from the mountains, and then the general turned and started toward the grand'case. His legs were short and a little bowed, perhaps from constant riding. As he began to mount the grand'case steps, he reached across his hip and hitched up the hilt of his long sword so that the scabbard would not knock against the steps as he was climbing. A sentry nudged the man with a bayonet and he moved forward and went after the black general.

On the open gallery the black general took a seat in a fanbacked rattan armchair and motioned the man to a stool nearby. When the man had sat down, the general said for him to say again those words he had begun before. The man swallowed once and began it.

Brothers and Friends, I am Toussaint Louverture. My name is perhaps not unknown to you. I have undertaken to avenge you. I want liberty and equality to reign throughout Saint Domingue. I am working towards that end. Come and join me, brothers, and fight by our side for the same cause.

The general took off his high-plumed hat and placed on the floor. Beneath it he wore a yellow madras cloth over his head, tied in the back above his short grey pigtail. The cloth was a little sweat-stained at his brows. His lower jaw was long and underslung, with crooked teeth, his forehead was high and smooth, and his eyes calm and attentive.

So, he told the man, so you can read.

No, the man replied. It was read to me.

You learned it, then.

Nan kè moin. He placed his hand above his heart.

Toussaint covered his mouth with his hand, as if he hid a smile, a laugh. After a moment he took the hand away.

From the beginning then. Tell me your name.

The whitemen called me Tarquin, but the slaves called me Guiaou?

Guiaou, then. Why did you come here.

To fight for freedom. With black soldiers. And for vengeance. I came to fight.

You have fought before?

Yes, Guiaou said. In the west. At Croix des Bouquets and in other places.

Tell me, Toussaint said.

Guiaou told that when news came of the slave rising on the northern plain he had run away from his plantation in the western department of the colony and gone looking for a way to join in the fighting. Other slaves were leaving their plantations in that country, but not so many yet at that time. Then les gens de couleur were all gathering at Croix des Bouquets to make an army against the white men. And the grand blancs came and made a compact with les gens de couleur because they were at war with the petit blancs at Port au Prince.

Hanus de Jumécourt, Toussaint said.

Yes, said Guiaou. It was that grand blanc.

There were three hundred of us then, Guiaou told, three hundred slaves escaped from surrounding plantations that les gens de couleur made into a separate division of their army at Croix des Bouquets. They called them the Swiss, Guiaou said.

The Swiss? Toussaint hid his mouth behind his hand.

It was from the King In France, Guiaou said. They told us, that was the name of the King's own guard.

And your leader? Toussaint said.

A mulatto. Andre Rigaud.

Toussaint called over his shoulder into the house and a short bald white man with a pointed beard came out, carrying a pen and some paper. The white man sat down in a chair beside them.

Tell me, Toussaint said.

Of Rigaud?

All that you know of him.

A mulatto, Guiaou told, Rigaud was the son of a white planter and a pure black woman of Guinée. He was a handsome man of middle height, and proud with the pride of a white man. He always wore a wig of smooth white man's hair, because his own hair was crinkly, from his mother's blood. It was said that he had been in France where he had joined the French Army; it was said that he had fought in the American Revolutionary War, among the French. Rigaud was fond of pleasure and he had the short and sudden temper of a white man, but he was good at planning fights and often won them.

The balding white man scratched across the paper with his pen, while Toussaint stroked his fingers down the length of his jaw and watched Guiaou.

And the fighting, Toussaint said.

There was one fight, Guiaou told. The petit blancs attacked us at Croix des Bouquets and fighting with les gens de couleur and the grand blancs we whipped them there. After this fight the two kinds of white men made a peace with each other and with les gens de couleur and they signed the peace on a paper they wrote. Also there were prayers to white men's gods.

And the black people, Toussaint said. The Swiss?

They would not send the Swiss back to their plantations, Guiaou told. The grand blancs and mulattos feared the Swiss had learned too much of fighting, that they would make a rising among the other slaves. It was told that the Swiss would be taken out of the country and sent to live in Mexico or Honduras or some other place they had never known. After one day's sailing they were put off onto an empty beach, but when men came there they were English white men.

This was Jamaica, where the Swiss were left. The English of Jamaica were unhappy to see them there, so the Swiss were taken to a prison. Then they were loaded onto another ship to be returned to Saint Domingue. On this second ship they were put in chains and closed up in the hold like slaves again. When the ship reached the French harbor they were not taken off.

Guiaou told how his chains were not well set. During the night he worked free of them, tearing his heels and palms, and then lay quietly, letting no one know that he had freed himself. In the night white men came down through the hatches and began killing the chained men in the hold with knives.

Guiaou covered his neck with his right hand to show how the old scars mated there. After several blows, he told, he had twisted the knife from the hand of the white man who was cutting him and stabbed him once in the belly and then he had run for the ladders, feet slipping in blood that covered the floor of the hold like the floor of a slaughterhouse. But when he came on deck the white men began shooting at him so he could only go over the side--

Guiaou stopped speaking. His Adam's apple pumped and he began to sweat.

It's enough, Toussaint said, looking at the tangled scars around Guiaou's ribcage. I understand you.

Guiaou swallowed then, and went on speaking. In the dark water, he said then, the dead or half-dead men were all sinking in their chains and sharks fed on them while they sank. The sharks attacked Guiaou as well but he still had the cane knife he had snatched, and though badly mauled he fended off the sharks and clambered out of that whirlpool of fins and blood and teeth, onto one of the little boats the killers had used to come to the ship. He cut the mooring and let the boat go drifting, lying on the floor of the boat and feeling his blood run out to mix with the pools of brine in the bilges. When the boat drifted to shore he climbed into the jungle and hid there until his wounds were healed.

How long since then, Toussaint said.

I didn't count the time, said Guiaou. I was walking all up and down the country until I came to you.

Toussaint looked at the bearded white man, who had some time since stopped writing, and then he called down into the yard. A barefoot black soldier came trotting up the steps onto the gallery.

Take care of him. Toussaint looked at Guiaou.

Coutelas moin, Guiaou said.

And give him back his knife. Toussaint hid his mouth behind his hand.

Guiaou followed the black soldier to a tent on the edge of the cane fields. Here he was given a pair of worn military trousers mended with a waxy thread, and a cartridge box and belt. Another black soldier came and gave him back the cane knife and also returned him his piece of cassava, which had not been touched.

Guiaou put on the trousers and rolled the cuffs above his ankles. He put on the belt and box and thrust the blade of his cane knife through the belt to sling it there. The first black soldier handed him a musket from the tent. The gun was old but had been well cared for. There was no trace of rust on the bayonet or the barrel. Guiaou touched the bayonet's edge and point with his thumb. He raised the musket to his shoulder and looked along the barrel and then lowered it and checked the firing pan. He pulled back the hammer to see the spring was tight and lowered it gently with his thumb so that it made no sound.

The other two black soldiers were almost expressionless, yet they seemed to have relaxed a little, seeing Guiaou so familiar with his weapon. Guiaou lowered the musket butt to the ground and looped his fingers loosely around the barrel. He stood not precisely at attention, but in a state of readiness.