From The Stone That the Builder Refused

Copyright Madison Smartt Bell (c) 2004 all rights reserved

Chapter 28

La Crête à Pierrot

The

little painted pendant went on troubling Maillart, for he couldn't determine

what to do with it. As it would

certainly be compromising to Antoine Hébert's sister, he ought probably to have

got rid of it-- tossed it into the canal with the rest of the trinkets out of

Toussaint's trophy box. The order

to treat any white woman who'd consorted with a black as a prostitute had rather

shaken the major. There'd be more

than one colonial dame brought low if that directive were broadly applied.

More than one of Maillart's own acquaintance.

He wondered too, what lay behind it, what other disagreeable orders there

might be.

And

still the pendant's image reminded him so of Isabelle that he could not quite

bring himself to dispose of it. It

was not her portrait, yet it recalled the brightness of her eyes, the coyness in

that finger laid over lips stung red by kissing.

At moments he thought private he'd cup the pendant in his hand and study

the image on the small ceramic disc, wondering where Isabelle was now, if she

had reached some place of safety. He

was confident she had, for Isabelle was a cat who fell on her feet, though by

this time she might have consumed a few of her spare lives.

He'd caught young Captain Paltre a time or two, peering over his

shoulder, trying to see into his palm, but then Maillart would fold his fingers

over the teasing face and drop the pendant back in his coat pocket.

He could not quite control the habit of worrying it between his thumb and

forefinger there, but the surface of the disc was thickly glazed, so that this

handling did not wear away the image.

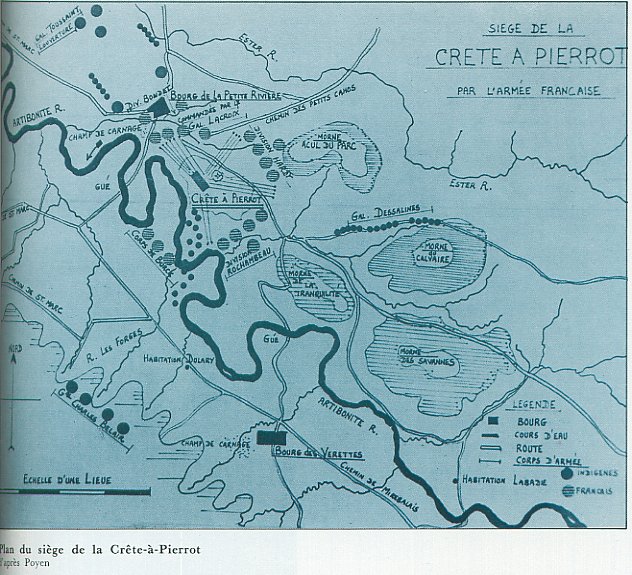

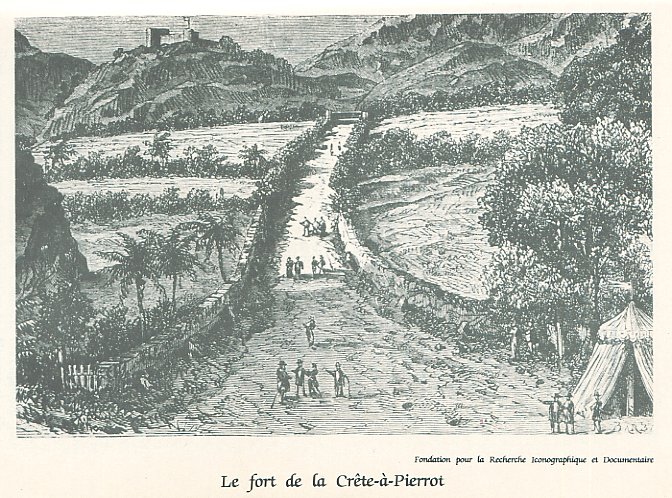

They'd

been on the march out of Port-au-Prince for several days, since news had come

that General Debelle had been pushed back, with surprising losses, from a little

fort above Petite Rivière. Maillart

knew the fort, and thought little of it. The

place was well chosen, to control a key point of entry to the interior via the

Grand Cahos, but the fortification itself did not amount to much, and though it

stood on a high cliff above the Artibonite River, it was too easily attacked

across the inconsequential slope rising from the town.

And

yet it seemed to be their target. Captain

General Leclerc appeared to believe that here Toussaint had gone to ground. Maillart did not much think so.

Toussaint did not willingly put his back to any set of walls.

But maybe he'd been forced to it; it might be true, and so the major kept

his opinion to himself. For the

past two days they'd been maneuvering inland, and General Boudet had detached

the advance guard to press as far east as Mirebalais, under command of the

adjutant-General D'Henin, who'd taken some losses capturing a small redoubt,

then found the town in ashes. D'Henin

returned to Boudet gray-faced, with a tale of three hundred white corpses

weltering in their blood where they'd been hacked to death on Habitation Chirry,

and all the countryside in flames.

Now,

toward the close of day, Boudet's reunited division moved along the south bank

of the Artibonite toward the town of Verrettes.

Maillart contrived to feel mildly optimistic on this ride, despite the

nervous whispering of D'Henin's men. He

rode along to Paltre's left, fingering the pendant in his pocket.

Verrettes was scarcely more than a village, but pleasantly situated not

far from the river, and there a major might commandeer a roof for the night,

perhaps even a bed. Perhaps there

would also be supplies to requisition. They'd

been travelling since Port-au-Prince on moldy biscuit from the ships.

Though Maillart had some skill in supplementing such rations, the pace of

their march had been brisk enough that he'd been able to supply himself with no

more than a few pieces of fruit.

His

stomach responded to the thought of a regular meal with a couple of interested

growls. Maillart tightened his

diaphram and stood up in his stirrups, peering ahead.

On the outskirts of Verrettes a skirmish line had appeared, and a few

shots were fired, though at such long range that the balls were spent when they

reached the French column. Pamphile

de Lacroix ordered the drummer to beat the charge.

The skirmishers, mostly un-uniformed fieldhands, scattered easily enough,

though some still sniped at the French flanks from the trees.

"We

are not so terrifying as we were," Lacroix muttered, as he made his way

back down the line to Maillart.

"That

band of irregulars presents us no real threat," the major replied.

"No,"

said Lacroix, with a distant smile. "But

I don't like their confidence.

The

departure of the skirmishers revealed a pall of smoke.

Maillart's heart sank. Verrettes

was burned too-- yes, the houses were destroyed from one end to the other, he

saw as they rode to the central square. The

Place d'Armes was carpeted with the bodies of white men, women, children.

Some preserved an attitude of supplication in their deaths, kneeling

slumped against the walls, their empty hands stretched out for mercy.

The blood was not yet dry on the ground.

Maillart saw a woman who seemed to have been slain by a bayonet or a

lance that had first passed through the trunk of the infant she held to her

bosom. He looked away quickly but

there was nowhere safe to look except for the darkening sky.

Captain

Paltre leaned sideways out of his saddle and puked on the ground, then

straightened and rode on, his eyes glazed, a trail of vomit at the corner of his

mouth. Maillart wished he would

collect himself enough to wipe it away. Paltre

had reported a similar scene when he'd entered Saint Marc with Boudet's

division, just shortly after Dessalines had put the town to bayonet and torch.

Apparently he was not yet hardened to such spectacles.

Buzzards

walked comfortably among the dead, shrugging their black wings, like old men

stooping in black tailcoats. From

their attentions, many of the corpses stared from empty eyesockets.

Against a tree in the center of the square, something flopped and

groaned. Lacroix hurried in that

direction, then called for a farrier to come with tools to draw the heavy nails

that transfixed the white man's palms to the living wood.

His swollen tongue hung out of his mouth. Maillart gave him a drink of water.

"Who

did it?" Lacroix said.

"Dessalines,"

the man said thickly. "This

morning, Dessalines was here." When

the second nail was drawn, he slumped to the ground in a faint.

"He

won't live," Lacroix said grimly.

"Most

likely not," Maillart agreed. He

was trying not to look at Paltre, who sat dumbstruck astride his halted horse.

Somehow the smear of vomit by Paltre's mouth distressed him more than all

this scene of carnage.

"My

Christ." Lacroix swept his arm

around the panorama. "The reports don't give one a proper idea...."

Maillart

said nothing.

"They

are not human," Lacroix said. "Whoever

did such thing cannot be human."

"Don't

say that," Maillart heard himself blurt.

"Never say it."

Lacroix

looked at him curiously, perhaps somewhat suspiciously, but Maillart said no

more. And anyway the order was

coming down the line to evacuate the ruined town.

He

had no appetite that night, not even for his ration of hardtack.

They camped on the south bank of the Artibonite, squared off in

battalions, to protect their equipment and horses at the center of each square.

At first the men had been moved to anger by the massacre, but after

nightfall, their humor turned uneasy. At

midnight, Maillart was roused by Paltre's nervous movements. Apparently there was a little gunfire around the edges of

their camp, and the sentries were shooting back into the dark.

"It's

nothing," Maillart snapped at Paltre. "They

won't attack us in this strength. They

only mean to steal your sleep."

With

that he rolled over, and flattened his cheek against the leather of his

saddlebag. But after all it was not

so desirable to reenter his nightmares just now.

He lay feigning sleep for Paltre's benefit, remembering what he had said

to Lacroix that evening. To declare the enemy less than human opened the door to every

horror. Dessalines must have told

himself the same today, before he put his victims to the bayonet: These

are not human. Maillart had not

been able to hold himself back from touching that woman, stabbed to the heart

through the child she held. He had

touched her on the cheek. The skin

had been warm, perhaps only from the sun, but it seemed to hold some fading

warmth of life.

....that they should have always before them the hell that they deserve-- a phrase from Toussaint's letter, which Chancy had been

caught carrying. If the message had

been intercepted, Dessalines was certainly acting in its spirit all the same.

And certainly there was a human intention behind it.

It was terrible, but not insane. In

fact it was quite a lucid intention, plain and bright.

Though he liked Pamphile de Lacroix a great deal, Maillart could never

say so much to him. It might after

all be taken for treason. Besides,

his own ideas confused him. He

wished Antoine Hébert were near. Antoine

would have known better how to put it. Really

this style of thinking was more in the line of the doctor than Maillart.

Maillart did not like it when his thoughts boiled so.

The activity of the thoughts stopped him from sleeping.

Or

even Riau, if Riau were here now. He

would say nothing on the subject, or very little, but Maillart thought Riau

would understand what he himself could not formulate.

Riau had a facility for acting and being without any sign of reflection,

and this the major had always appreciated.

But Riau had taken a message to Croix des Bouquets and had never come

back from that errand.

Maillart

sat up suddenly. Of course, Riau had gone back to Toussaint.

He had known it from the second day Riau failed to return to

Port-au-Prince, but had not recognized the knowledge.

Well, there was nothing to be done about it.

The next time he and Riau met they probably would be obliged to try to

kill each other. Such was the soldier's lot.

But tonight, Maillart felt resentful of it. It seemed more difficult to shrug it off than it had been

when he was younger. This

obligation was the most atrocious aspect of it all, he thought.

But it could not bear much more thinking.

Eclair

snuffled across the earth toward him, raised hiss head and whickered.

Maillart clucked his tongue, stretched out again, balanced his head on

the saddlebag. Above him, stars

revolved in spirals. Eventually he

slept.

In

the morning a handful of deserters from Toussaint's honor guard crossed the

river, meaning to come over to the French.

They'd lured their captain along on some pretext, though apparently he

was not privy to their scheme to change sides.

Among this party, Maillart recognized Saint James, one of the very few

white men who rode in Toussaint's guard. By

Saint James' account, discreetly murmured to Boudet and his staff, Dessalines

had recently conducted at Petite Rivière a slaughter similar to the one they'd

just come upon at Verrettes.

Boudet

had been in a cold fury since the evening before, and at this news he rounded on

the captain, who had been arrested but not yet restrained.

"How many men have you murdered at Petite Rivière!"

With these words Boudet snatched the captain's arm.

They struggled, chest to chest-- then Boudet sprang back with a cry.

He had been bitten in the thumb, bad enough to bleed.

The captain meanwhile rolled under the belly of the horse from which he'd

lately dismounted, scrambled through the legs of other horses, and ran full tilt

for the river. He was a good

swimmer, Maillart took note, and a swift one.

Though musket balls ploughed up the water all around him, none of them

seemed to find a mark. The captain emerged on the far bank and went on still at a

run. Some were still shooting at

him, though the range was doubtful. Maillart

had his own pistol drawn but did not discharge it. Then the black captain's running stride developed a hitch.

A lucky shot must have struck his leg.

Awkwardly slowing, like a loosewound clock, he managed a few paces more

and then collapsed.

"We'll

get him when we cross the river," Boudet said.

Saint

James and the other men who'd come with him led Boudet's division up the river

to the ford they'd used themselves that morning.

Snipers harried them from the woods as they marched, and a few horsemen

rode feints along their flanks. Maillart

learned from the scouts that these were men of Charles Belair, the same who had

broken his sleep with their raid the night before.

Boudet's troops were hot to pursue these harassers.

After what they'd seen the day before they wanted blood. But Boudet and Lacroix kept them close in their ranks and

marching forward.

On

the north bank of the ford the enemy appeared in sufficient force to trouble

them with musket fire across the river. Boudet

formed his advance guard under command of Pétion, and ordered him to lead the

crossing. A number of Pétion's

grenadiers were grumbling that it was always they who had to march in the van

and risk the fire of ambushes. Pétion

turned on them and snapped, "It is your glory to have this place of honor--

now be silent and follow me."

Indeed,

Pétion was the first man into the river and the first man across.

Maillart watched him with an interested respect.

Pétion was a mulatto and an old Rigaudin; he'd just come out from France

on the same boat that carried Rigaud and his other partisans.

He looked to be quite a capable and courageous officer, though Maillart

was content, for his own part, to be marching well behind the vanguard.

He

joined the detachment that returned to the area of the bank where that black

captain had fallen. Though the

leaves where he'd lain were all soaked with his blood, the man himself was

nowhere to be seen. Maillart

supposed someone must have carried him off, for by the amount of blood soaking

the ground, he'd have been to weak to shift on his own.

Angry at his escape, a few of the soldiers kicked up the bloody leaves.

The

ambushes had been swept away by the time they rejoined the main advance.

Boudet and Lacroix and most of the men were eager to press on to Petite

Rivière, where they hoped they might engage Dessalines.

But Saint James and the others who'd deserted with him told the French

generals of a large powder depot in the vicinity, and Boudet decided it would be

best to capture it if possible.

With

Belair's raid, many of the men had got little sleep the night before, and

marching under the full sun told on them quickly now. Soon their heavy wool

uniforms were sweated through, so that all of them smelled like soggy sheep.

In the mountains the trails became too steep and narrow for them to

continue dragging their few cannon. Boudet

called a halt to bury the artillery, that the enemy might not discover it. Despite these delays, they reached Plassac a little before

noon.

A

howling came from across the gorge from them-- some number of black irregulars

appearing on an open bend of the trail that climbed the opposite hill.

Lacroix shaded his eyes to look.

"Can

it be Dessalines?" he said.

Maillart

accepted the spyglass Lacroix offered him and squinted into if for a moment.

"I recognize no uniforms," he said as he lowered the

instrument. "These might be

anyone, but--"

"If

we could only come at him now...." Lacroix

was flexing both his fists.

"Blow

up the magazine," Pétion said. "That

will hurt them as much as anything, whoever they may be."

Boudet

nodded, then gave his orders. A

couple of Pétion's grenadiers laid the fuse, as the rest of the troops marched

down the defile. Maillart turned

his head as he passed and saw the flame hissing backward.

At the bottom of the descent they halted and looked back to see the

magazine erupt from the mountainside with a tremendous flash and roar.

A little stone dust rained down on them.

A few of the men cheered, while others cursed Dessalines.

The echo of the explosion persisted in Maillart's ears as they went on.

He could just see the last of the black irregulars rounding the bend of

the trail out of range above them, like the tail of a banded snake slipping into

the jungle. They saw no more of the enemy for the rest of that day,

though sometimes they were fired upon from cover.

At sundown they had come within a cannon shot of La Crête à Pierrot.

Doctor

Hébert came awake at first light, with the unpleasantly startled feeling

familiar to him since the killings at Petite Rivière.

He lay face down, palms flat on the mat, until his heartbeat slowed.

Under his hands was the softness of the earth he'd broken to bury his

weapons. At last he sat up and

sniffed the damp air. The chatter

of crows came from beyond the parapets. He

wished for coffee, uselessly. Rations

were already short. General Vernet

had not been able to supply them with the quantity of water expected. And the night before, Dessalines had returned to the

fort in a towering rage. A French

advance had crossed the river near Verrettes and cut him off before he could

reach Plassac; he'd been unable to resupply from the powder magazine there, and

feared the French might have discovered it.

Amidst

the crow talk began the thin scrape of a violin tuning.

The doctor wished the man would desist.

His head ached slightly, for want of coffee.

He got up, though, and walked toward the sound.

The naturalist Descourtilz squatted by the wall talking to the violinist.

Dessalines had brought in an odd assortment of Toussaint's musicians the

night before: two trumpeters, a drummer and the violinist-- white men all.

It seemed that Toussaint had abandoned his whole orchestra on some

plantation nearby, in the hurry of his march north.

The others had tried to get away to the coast, but these four had stayed

behind, to be scooped up by Dessalines.

The

doctor knew the violinist, from Toussaint's fêtes at Le Cap.

What was his name? Gaston,

possibly. He nodded, rendered a thin smile. Bienvenu also looked on, fascinated, as Gaston scraped his

bow across the strings. The other

musicians lay sprawled and snoring beside their instruments on the ground.

"Look

there." Descourtilz tilted his

chin toward one of the embrasures. The

doctor peered along the cannon barrel. Tucked in the river's bend, below the

fort, was a long column of French soldiers marching toward the trees that

screened the town of Petite Rivière. The

doctor felt a certain chill. He

took his face away from the embrasure, lips formed in a silent whistle.

"Yes,"

said Descourtilz. "That looks

to be an entire division."

"I

think you're right," said the doctor.

"Most likely they are maneuvering to attack from the direction of

the town."

"A

pity Dessalines has come." The

naturalist looked pale and shaky. "He'll

murder us before he'll see us rescued."

The

doctor shook his head as he glanced at Gaston.

Better to leave such thoughts unvoiced.

If the violinist was alarmed at Descourtilz's remark he did not show it,

but went on scraping out some melancholy air, under Bienvenu's rapt gaze.

"Come,"

the doctor said to Bienvenu. "Let

us build up the fire." There

some wounded men to be tended, from the engagement with Debelle a few days

before. His own head wound needed

its dressing changed also, though now it was nearly closed.

Descourtilz might lend some assistance and take his mind of his fretting. But Descourtilz was staring at the powder magazine.

"Christ,"

said the naturalist. "Now

what does he mean to do."

Dessalines

was striding up toward the magazine, a blazing torch in his right hand.

Lamartinière and Magny walked on either side of him.

The few hundred soldiers of the garrison followed, like iron dust drawn

by a magnet.

Dessalines

pushed open the door to the magazine and peered inside.

A sulphur smell came wafting out, wrinkling the doctor's nose.

The torch in Dessalines' hand sputtered and sparked.

Descourtilz flinched against the wall and reflexively covered his ears

with his hands.

"Open

the gate," Dessalines said in a ringing voice.

At the lower end of the fort, two puzzled sentries swung the two halves

of the gate slowly outward.

Dessalines

sat down on a pyramid of cannonballs beside the magazine's open door.

He held the torch with both hands between his knees and narrowed his eyes

on the flame. Now he spoke in a

much lower tone, so that everyone must press closer and lean in to hear him.

"I

will have no one with me but the brave," he said.

"We will be attacked this morning.

Let all who want to be slaves of the French again leave the fort

now."

He

thrust the torch with both hands toward the open gate.

A few heads turned, but no man moved in that direction.

"I

don't suppose we are included in that invitation," Descourtilz muttered.

Gaston, who'd lowered his violin, merely gaped.

"Let

those with the courage to die free men stay here with me," said Dessalines.

A

cheer went up: We will all die for

Liberty! The doctor noticed

that Marie-Jeanne, Lamartinière's wife, cried the affirmation as loud as any

man. She was a tall and striking

colored woman; he was rather astonished to see she was still here.

"Quiet."

Dessalines chopped a hand in the air to cut off the cheer, then swung the

torch toward the magazine's open door. "If

the French get over the wall, I will blow them all to Hell, and us to Guinée,"

he said. "Now, all of you, get

down against the walls, and no man let himself be seen."

In

the cool damp of the early morning, Maillart got up and washed his face in the

river and moved out in the midst of Boudet's column, his bones a little creaky

from sleeping on the ground. On the

cliff above them, the unremarkable fort was quiet, half-hidden in lifting swirls

of morning mist. Boudet's men filed

into the strip of woods outside Petite Rivière.

A stench of smoke and scorched flesh lowered over them; this town had

been burned, like the others.

Boudet

called a halt outside the town. With

Pétion, Maillart and Saint James, he rode out of the ranks up the low grade

until they were just out of musket range of the first earthwork, outside the

fort. Cannon mouths showed at the

embrasure, but no guard was visible anywhere.

There was no flag flying anywhere, though Maillart thought he could pick

out a thin thread of smoke rising somewhere within the walls.

Boudet

scrutinized the position with a spyglass. "It

looks deserted," he declared. "These

murderers will not stand to fight. I

think they've spiked their guns and run away."

"Beware

an ambush," Pétion said softly.

"What

ambush? Their defenses are all

apparent here."

The

sun broke fully over the peak of the hill and the walls of the fort.

Raising one hand, Boudet shaded his eyes against the blaze.

"Leclerc

is supposed to come out from Saint Marc to join us," he said, twisting in

the saddle to look toward the west. "No

sign of him as yet.... I think we

may as well take this place. We'll

carry it, if it's manned or not."

They'd

ridden halfway back to their ranks when firing began in the trees to the west.

Pamphile de Lacroix, scouting through the woods above the town, had come

upon an enemy camp and, as it seemed at first, routed it.

The blacks were in full flight as they broke from the trees and rushed

across the open slope toward the fort, with the French troops pursuing them full

tilt, already hooking and thrusting with their bayonets.

Boudet

gave a quick order to send his own men into the charge.

Maillart could feel the force of their rage as the first line swept

around his horse. This charge would wipe out the shame and horror of the

Verrettes massacre, wash all that away in blood.

But then the fleeing blacks all jumped down into the ditches and the

cannons of the fort belched out mitraille

across the suddenly cleared field.

A

hundred men must have gone down in that first volley.

Maillart's heart flipped over in his chest.

But the line closed up its gaps at once and kept advancing, the pace of

the charge barely slackened, all the way to the edge of the first ditch.

"There,

there! is that Toussaint?" It

was Captain Paltre who spoke, jockeying his horse up to Maillart's.

The

walls of the fort now swarmed with the enemy.

Dessalines appeared on the rampart, brandishing a sword in one hand and a

torch in the other. He'd

stripped off coat and shirt to show his scars, but still wore a tall hat with

fantastic plumes.

"It

is Dessalines," said Maillart, "but he will do."

He drew his pistol. A dozen

shots were fired at the black general at the same time as his, all of them

without effect. By the legs of

Maillart's the dancing Eclair a couple of grenadiers, felled by mitraille,

were trying to drag themselves backward, but the infantry line trampled them

down as it moved ahead. Paltre

galloped his horse to the rim of the first ditch, jumped down, and with a wide

sweep of his arm skimmed his hat beyond all the earthworks, over the wall and

into the fort.

"Follow

me," he called out hoarsely, and plunged into the ditch.

Amazed, Maillart saw him emerge on the other side.

He crossed the other ditches miraculously unharmed and pulled himself to

the top of the wall. About thirty

other grenadiers had followed him, making a wedge across the ditches.

Maillart rode to the edge of the earthworks, undecided whether to join

the assault on foot. On the

rampart, Dessalines split a man's head with his sword and at the same time

jabbed his torch into the face of another soldier assailing him.

Maillart loosed his reins to reload his pistol. Another

grenadier reached the top of the wall and was pierced by ten bayonets at once.

A black smashed Paltre in the face with a musket stock and Paltre

crumpled over backward into the ditch. Another

round of mitraille roared from the cannon.

Maillart's horse bucked and threw him.

He

floundered on the edge of the ditch, fumbling to recover his pistol among the

milling feet of the infantry. The

charge had broken under the last round of mitraille.

Paltre came swimming up from the ditch, his face pouring blood from a

broken nose. Maillart caught the

back of his collar and hauled him out. He

stood, supporting Paltre with one hand, the unloaded pistol dangling from the

other. All around him the ranks had

been shattered into complete disorder.

From

the walls a trumpet sounded, a drum rolled and the gate swung open.

Laying planks across the ditches, the blacks now charged the French with

their bayonets. In the melée,

Maillart's horse brushed by him and he managed to catch the trailing reins. He mounted and dragged the half-stunned Paltre across the

withers. Halfway down the slope the

French had reformed and returned to the charge, repelling the blacks, pursuing

them again. Again they disappeared

into the ditch, and this time the volley of mitraille

did such terrible damage that the French could not rally.

Maillart

saw General Boudet sitting on the ground, hands wrapped around the toe of his

boot and blood streaming through the fingers.

He rode toward the wounded general, but before he could reach him another

horseman had caught him up and was carrying him out of the fray.

Behind the retreat of their general, the French line completely

shattered. Again the trumpet

sounded from the walls, and this time it was answered from the forest to the

west. Out of trees came galloping

several hundred horsemen of Toussaint's honor guard, sabers shining in the full

morning light.

Maillart

recognized Morriset at the head of the cavalry, and he thought he saw Placide

Louverture riding behind. He drew

his own saber. But he was

encumbered by his wounded passenger, and the French infantry had been stampeded

completely by this fresh cavalry charge. Nothing

for it but to ride to the rear, if there was any rear to ride to. Morisset's horsemen pursued the French to the town and into

the plain beyond it. For a few

dreadful minutes Maillart believed that Boudet's whole division was about to be

completely destroyed. But then they

found themselves supported by Leclerc himself, just marching in from Saint Marc

with Debelle's division, now commanded by General Dugua.

Maillart

deposited Paltre behind the newly solidified infantry line.

At the sight of the French reinforcement, Morisset had withdrawn his

cavalry up the Grand Cahos road. The

French advanced again, to the town and beyond, and halted just out of range of

the fort's cannon. Now the French

tricolor flew from the walls. From

within the fort came wild shouts of triumph from the blacks.

The wide slope below the ditches was strewn with six hundred French

corpses.

In

the moment before the battle was joined, Dessalines had stirred up the sleeping

musicians from the ground with the point of his sword.

It would be a rough awakening, the doctor thought, to open your eyes to

Dessalines bestriding you, probing your ribs with his blade, a torch smoking in

his other hand, his old whip-scars writhing on his back like fat white snakes.

When Dessalines bared his torso for a battle, it was a bloody sign.

But

at first Dessalines seemed in great good humor, as if he anticipated some fine

entertainment, a favorite dance like the carabinier. He tickled the musicians into a row, though he did not yet

command them to play. The doctor

watched from the shade of his ajoupa,

Descourtilz crouching beside him there. The

cannoneers squatted low beside their gun carriages.

At Dessalines's signal, the fuses had been lit.

Outside

the fort came a roar like the wind. The

French troopers were shouting their indignation as they charged.

Descourtilz got up to peer over the wall, and the doctor cautiously

followed suit. He was in time to

see the retreating black skirmishers dive into the ditches just under the walls.

"Feu!"

Dessalines voice boomed, almost simultaneously with the cannon.

The guns recoiled and the air filled with burnt-powder smoke.

Grapeshot tore great gaps in the ranks of the French.

A week previously, Debelle's troops had broken at this moment, but these

new soldiers did not falter. They

closed their ranks, and when the second volley laid waste to them again, they

closed ranks once more and kept advancing.

At

the first volley Dessalines had prompted the musicians to strike up a martial

air by smacking them on the calves with the flat of his sword.

The drum and trumpets made themselves faintly heard, but the violin was

completely inaudible over the noise of artillery, however desperately Gaston

sawed it. Dessalines moved behind

the players, grinning. The French

advance had come to the edge of the ditches.

The doctor saw an officer with a dimly familiar face sail his hat over

the walls of the fort, then charge after it, with some shouted exhortation.

There was a humming around his head, like bees; he didn't realize it was

bullets till Descourtilz pulled him down from his perch.

Together

they crawled toward the wall of the powder magazine for better cover.

But Dessalines, who'd lost his smile, had resumed his post by the open

door. "Turn them back!"

he shouted, "Or--" He

shook his torch toward the open doorway. Half

a dozen French grenadiers had reached the top of the wall and were fighting hand

to hand with the defenders there. Dessalines

appeared to change his strategy; with a shout he rushed into that fight.

The doctor saw him dance atop the wall.

A bullet sheered off one of the tall feathers in his hat, but except for

that he seemed untouchable.

Then

Dessalines came panting back and ordered the musicians to sound the charge.

Unbelievably, the gates were pushing open for a sortie.

The doctor risked another peep over the wall.

Now it was Dessalines' men chasing the French down the slope, jabbing

bayonets in their kidneys. The

French made a rally, turning the tide, but mitraille

blew away this charge like the others, as the blacks again took cover in the

ditches. And now, as the trumpets

continued to blare, Morisset led the cavalry out of the woods to sweep the

field.

The

doctor dropped down to the earth of the fort.

Though the cannons had quieted, his ears still rang.

Descourtilz hunkered by the ajoupa,

scraping together a heap of the musket balls that lay on the ground like

hailstones. Finally the trumpeters

stopped blowing, one of them laying his palm over his deflated chest as he

lowered his instrument. Dessalines

was leading a cheer, stabbing his torch high into the air.

Black soldiers in the highest state of excitement were dancing their

victory on the edges of the parapets.

Bienvenu returned to the doctor, breathless, sweating, streaked with

blood that seemed not be his own.

See

to the fire, the doctor reminded himself, and the herbs and poultices and

bandage rolls. Behind Bienvenu came

the fresh wounded; there would be much work to do.

Captain

Daspir was riding with Leclerc's staff when they met Boudet's division in near

complete rout by the black cavalry, a hundred yards below Petite Rivière.

There passed a moment of sick confusion; then Daspir and Cyprien set

themselves to rallying the fresh troops into squares, as the fleeing men took

cover behind them. In fact the

cavalry charge did not press them very hard once their lines were well-formed,

but retreated up the road west of the town.

"What

is the meaning of this?" Leclerc was sputtering.

"You yield before these unorganized savages?"

He

was berating General Boudet, who came hopping toward him on one leg, supported

by a lieutenant on his left, his hurt leg swinging, his face drawn and pale with

pain.

"See

for yourself," Boudet said through his gritted teeth, and sank to a sitting

position on a cartridge case. A

surgeon knelt before him and began cutting away the blood-stained leather of his

boot.

"Forward,"

Leclerc ordered, trembling. Daspir

and Cyprien joined the march, which proceeded south of Petite Rivière.

In the ravines between the town and the river they discovered the

putrefying corpses of several hundred slaughtered white civilians.

Some of the men began to curse, others to vomit, but Daspir had no

reaction left in him, after similar scenes at Saint Marc and elsewhere, although

here the odor was most unpleasant, and the corpses hopped with vultures and

crawled with flies. He exchanged

one stupefied glance with Cyprien and rode on.

Presently they reached a new scene of carnage: hundreds of fresh-slain

French soldiers carpeting the slope below la Crête à Pierrot.

Stunned

silence obtained as the men moved into line.

Above, the noon-day sun was broiling.

Within the fort, the French flag snapped on a long staff.

Cries of mockery came from the walls.

Daspir's heart thumped uncomfortably against his ribs.

His mouth was brassy; he took a sip of tepid water from his canteen.

The black cavalrymen had also flown the tricolor, he remembered.

A youth with a red headcloth had carried it into the charge.

Leclerc

shook his head slightly as he surveyed the field, his small, delicate features

stiff with anger. "We will

avenge these men within the hour," he said, then turned to Daspir and

Cyprien. "Go back and bring up

the ammunition wagons. Who commands

in Boudet's stead, Lacroix? Let him bring what men he finds able to the field."

They

left Leclerc conferring with General Dugua, who had assumed the wounded

Debelle's command. Their detour to

avoid the ravine of the massacre brought them nearer to the dully smoldering

ruins of the town. Cyprien covered

his face with a scented handkerchief; Daspir simply tolerated his cough as they

passed. He rode toward the supply

wagons, but paused a moment to watch the surgeon working over Boudet's foot.

The general had had his toes shot away, it appeared, and he also had a

nasty suppurating wound on one hand. Behind

him, a weathered-looking officer with long mustaches and a major's epaulettes

was remolding a captain's broken nose between his thumb and forefinger.

Daspir took a second glance at the wounded captain and recognized the

disfigured Paltre.

"My

God, what has happened to you?" Daspir

jumped down from his horse at once. Paltre

made an effort to answer but could only spit out blood.

"Be

still," Maillart said, and turned to Daspir.

"It's all from his nose, he won't die of it.

A friend of yours? He's a

lucky man, and a brave one too-- if not a bit of a fool.

You might go get his hat for him, if you're returning to the

attack."

"His

hat?"

Maillart

straightened and offered his hand; Daspir clasped it briefly.

"He

threw his hat into the fort and tried to go after it," Maillart said.

"It's a miracle he's hurt no worse than this.

I think every man who followed him died."

Daspir

gaped. Paltre struggled up and spat

out more blood.

"I'm

going," he said. "If Daspir goes I go back too."

"Calm

yourself," Maillart said. "You've

proved your courage! You can't go

on till the bleeding stops. There's

no sense in it."

Daspir

opened his mouth to explain their bet and the competition.

Was it likely Toussaint was in that fort?

Leclerc had certainly thought to find him when they marched this way from

Saint Marc. He would have asked

Paltre to confirm it, but at that moment Cyprien rode up to remind him that he

should be hurrying the wagons up to the line.

The

fort was silent, motionless, though the cannon mouths breathed a little smoke,

and Maillart's ears still hummed with the din of the recent battle.

The carpet of dead men on the slope appeared to wriggle.

Maybe it was only the shimmer of the broiling noon heat. But no, a couple of wounded men were trying to crawl down the

slope to the new French line. Three

men broke from Leclerc's ranks to help them, but one was immediately picked off

by a marksman hidden in the fort-- dead before he hit the ground, though his

heels still drummed in the dust. The

other two soldiers shook their fists as they skipped back. Another long shot dispatched one of the wounded men who'd

kept on crawling.

There's

a man with a rifle, Maillart thought. He

considered his friend Antoine Hébert, such a surprisingly good marksman with

his long American gun. The notion

momentarily froze him, but of course the doctor would not be anywhere near this

place and in any case would not be firing on the French if he were; he was

always reluctant to use his unexpected talent against human life.

But surely the sniper in the fort must be armed with a similar weapon.

Leclerc

had brought a good number of black troops with him out of Saint Marc, men of the

Ninth Demibrigade, incorporated into Debelle's force after the surrender of

Maurepas. Some hailed from the Thirteenth Demibrigade was well.

Leclerc had put them in the front line, but they seemed a little

reluctant to advance across this killing ground.

Maillart knew these were no cowards.

He had trained some of them himself, in earlier days, when Toussaint

first began to organize a real army. Under

Maurepas they'd repulsed both Debelle and Humbert, defeated them really, and

inflicted considerable losses too. In

fact, Maurepas might never have surrendered if Lubin Golart had not turned his

coat and joined the French generals. Golart

had been a subcommander of the Ninth and was able to bring his regiment over to

the French; he'd hated any partisan of Toussaint's ever since the War of Knives;

and moreover he knew the terrain around Port de Paix as well or better than

Maurepas. These men of the Ninth

were brave and well-trained, Maillart knew, well-seasoned in battle also, and if

they hesitated now it was because they knew what was going to happen.

As

Leclerc should have known also, or at least Dugua.

Maillart's mind began to race. He

was still quivering from the shock of Boudet's rout and his own forced flight

before that cavalry charge. The

same thing that had happened to Boudet this morning must have happened to

Debelle the week before. Dugua

ought certainly to have learned that much when he assumed Debelle's command. Now Leclerc was reforming his line, replacing the black

troops with French, who were all more than eager enough for a charge.

Leclerc was going to march blithely into the same trap for a third time.

A

mostly naked black man appeared on the wall of the fort, wearing Paltre's hat,

and a rag of a breechclout. He

capered like a goat on the parapets, dancing the chica,

wriggling his spine and flapping his arms, thrusting out his chest and hooking

his pelvis upward. From inside the

walls came clapping and chanting and laughter.

The man's muscles gleamed as if they had been oiled. A few men fired from Leclerc's lines, unbidden, but he

ignored the shots. Finally he

turned his back and gave his buttocks an infuriating wriggle before he jumped

down into shelter behind the wall. The

hat was raised once more, twitched teasingly, before it disappeared.

"Take

that fort!" Leclerc, livid with rage, was screaming.

He stepped ahead of his line, whipping his sword forward and down.

At once the line swept past him. Drums

beat the charge. Maillart watched

Captain Daspir riding into the stream. He

held his own horse back. Someone

bumped against him-- Paltre, who'd managed to remount.

His nose was held in place with a blood-soaked bandage which gave him the

look of a demented agouti.

"I'll

get my own hat back," Paltre muttered, and rode on.

Maillart

grasped at him, angry-- he was moved to pursue, but held himself in.

Better not to let his anger sweep him along, as it was sweeping everyone

else on the field. He had never

liked Paltre much anyway, not since the days of Hédouville, but today he'd been

impressed with the young captain's lunatic bravery.

And since he'd invested something in saving Paltre's life, he didn't like

to see it wasted now.

Still

he stayed where he was and watched, a little surprised at his own detachment.

Leclerc's small, incongruously dapper figure was setting an example for

his men. He was well to the fore,

his life on the line, urging, encouraging.

It was what Napoleon would have done, in the days when his men worshiped

him as the Little Corporal. Maillart

had heard those tales from a distance. The

men who'd landed at Port-au-Prince with Boudet were full of them. But

it was an ill moment for Leclerc to be enacting such a dream, however bravely.

This charge was driven by rage, contempt, and incomprehension of the

enemy. Most of the troops had been

piloted over the country by overseers or landowners of Arnaud's old stripe, who

still somehow managed to believe they had only to show their slaves the whip to

return them to abject submission. In

the end it was misleading guidance.

The

former slaves stood calmly, neck deep in the ditches before the fort, elbows

bracing their muskets on the ground. They

held their fire till the very last moment, and when they did fire the effect was

withering, yet the French charge did not abate.

Now it was all hand to hand fighting in those trenches, and the momentum

of the charge had carried a couple of dozen grenadiers to the base of walls. But now, of course, came the mitraille,

mauling the French advance beyond the ditches.

The storming party was cut off, and would be slaughtered.

"Look

there." It was General Lacroix,

leaning into Maillart's shoulder and pointing as he shouted in his ear, toward a

small round hilltop north of the fort, covered by a sparse grove of slender

trees. "Do you see that

eminence?"

Maillart

nodded.

"Take

the seventh platoon of musketeers there," Lacroix said. "I'll wager

you can do some damage from that place."

Maillart

saluted; Lacroix thumped his shoulder and moved on.

The maneuver was accomplished quickly enough, and proved to have been

very well-conceived. From the

little hilltop Maillart could see plainly down into the fort, boiling like an

anthill disturbed by a boot. After

a moment he discerned that no cannon were aimed to cover the hill, and that

Dessalines sat on the step of the powder magazine, conducting the fight with a

lit torch he held in his right hand.

"Kill

that general," Maillart said, and fired his own pistol among the muskets,

but too quickly. The range was a little long for these small arms; cannon

would have been more useful. Dessalines

lifted a hot musket ball from the ground at his feet, then smiled up at the

hilltop. At once he got to his feet

and ordered two cannon to be rolled to the embrasures facing the hill.

Maillart

reloaded, fired again, again to no effect.

Either the range was simply too long or Dessalines was protected today by

some enchantment. He could hear the black general's voice very plainly,

bullying his cannoneers--what do you mean

by this sluggishness! Yet they

seemed to be bringing the guns around quickly enough.

One of Maillart's musketeers jostled him and pointed.

Beyond the fort, below the bluff, some hundreds of black irregulars were

climbing from the river bank onto the main battlefield to attack Leclerc's left

flank. It was not a very

well-organized movement but there were a lot of men involved in it, and

Leclerc's men were already falling into disarray under the constant battering of

mitraille.

Dessalines

grinned, and over his shoulder Maillart noticed a miserable quartet of white

musicians sweating out one of his favorite martial airs, and unbelievably he

thought he got a glimpse of Doctor Hébert flashing from the cover of one ajoupa

to another, a roll of bandage trailing from his arm. He most definitely saw Dessalines, himself, lower a flame to

a touch-hole. Mitraille snapped the slender trunks of half the little trees on

their hilltop. One of the

musketeers dropped to the ground, clutching his knee.

"Retreat!"

Maillart saw to it someone helped the wounded man away.

There was no hope for this position once cannon had been brought to bear

on it, though it might be worth trying to return with their own artillery.

Mitraille still raked the main battlefield below the fort.

Returning, Maillart saw Daspir's horse shot out from under him.

He rode in. Daspir was

pinned, one leg caught under his saddle and the horse's withers, trying to pry

himself loose with his sword. As

Maillart reached him, the horse rolled away.

Daspir's leg must not have been too badly hurt, for he was able to

scramble up behind with a little assist from Maillart's arm.

Excellent,

Maillart thought, now I own two of these reckless puppies.

He looked around but did not see Paltre.

To the left of the field, the new black irregulars were enthusiastically

bayoneting those of Leclerc's troops too bewildered by the mitraille

to resist in an organized way. In

fact, the whole situation was fast becoming desperate. General Dugua, bleeding in two places, was being carried off

the field on a stretcher. Pamphile

de Lacroix had joined Leclerc, and Maillart spurred his horse in that direction.

Behind, Daspir lurched off-center, then quickly regained his balance,

pressing his chest into Maillart's back.

Morisset

had made it a point of honor for Placide to carry the flag he'd captured in that

last raid on Gonaives into all subsequent engagements.

Sawed short for the purpose, the flagstaff could be seated securely in a

long scabbard strapped to the saddle, leaving Placide's hands free to shoot or

strike. In the first charge of that

morning, he'd fired no shot and struck no blow, though he'd ridden down several

of the bolting French troopers, and maybe they'd been killed by the hooves of

his horse, or finished off by others riding behind him.

When

the column of fresh troops appeared from the west, Morisset had pulled his

cavalry out of the battle; they rode to the shelter of the woods beyond the town

to rest their horses. Placide got down and walked his mount to cool for half an

hour before he let it drink. This

reflexive action calmed him as much as it did his horse.

He unfastened the red headcloth Guiaou had given him, mopped off his face

with it, and folded it in a triangle to put in his pocket.

The electric thrill of the fight still ran all through the guardsmen; the

grove was heavy with the odor of their anger and sweat, mingling with the hot

smell of the horses.

Only

one squadron of cavalry had entered the first charge; the second, commanded by

Monpoint, waited in reserve. The

two commanders watched the second French advance on the fort from the cover of

the trees.

"Which

one is Leclerc?" Monpoint asked Morisset, but neither man had ever seen the

French general.

"There,"

said Placide, pointing to where Leclerc had just stepped out of the ranks, to

initiate the charge. Morisset

grunted an acknowledgement. He

shaded his eyes to squint at Leclerc where he stood with Dugua, directing the

battle.

Somehow

the sight of Leclerc drained Placide of all feeling, even that uncategorizable

quaver that the recent action had left in his limbs.

He felt as empty as a bottle, washed and let dry.

Through this emptiness, action might flow without thought. When the French charge faltered at the ditches, and Gottereau

had brought his throng of armed fieldhands to take their share in the slaughter,

Monpoint began mounting the men of his squadron for another charge.

"Let

me ride with them," Placide said suddenly.

Morisset

looked at him, uncertain at first. Placide

turned into the wind, opened his headcloth into the air that fanned back over

his head, and tightened the knot on the base of his neck.

"Go,

then," Morisset said. "Do

you need a fresh horse?"

Placide

shook his head. "No, mine has

rested." Though the bay he

rode was not Bel Argent, it did come from Toussaint's personal stable, and

Placide thought it stouter than most of the honor guard's horses, though the

guard was generally well-mounted. Morisset stretched out a hand and brushed the knot of the

headcloth, letting his hand slip down from Placide's shoulder as Placide trotted

away.

They

entered the field at a gallop from the Grand Cahos Road.

Placide, a length behind Monpoint, managed the staff of the flag with his

left hand and the reins with his right. At

the first shock he seated the staff in the scabbard, switched hands on the

reins, and drew the sword Napoleon had given him.

His eye had tightened on Leclerc from the moment they rode into view.

Later he would reason through his motives: how Toussaint always took care

to blame Leclerc personally for this war, rather than the French nation or its

leader. How strangely suitable it

would be all the same for Leclerc to be struck down with the weapon Napoleon's

treacherous hand had placed in Placide's. But

at this moment there was no such notion in his head; there was nothing at all,

only the wind flowing in and out of the bottle.

Maillart

was a dozen yards away when the little group surrounding Leclerc disappeared in

a cloud of dust. At first he thought the Captain-General had been directly hit

by a cannonball or an exploding shell. Later

on it turned out that the ball had struck somewhat short and thrown up a

fist-sized stone into Leclerc's groin; not a lethal injury but more than enough

to flatten him. Daspir picked him

out first where he lay, and scrambled down from Maillart's horse, landing at a

run. He'd managed to hang onto his

sword amid all the confusion when his own horse had been shot down.

Now the trumpets blared from the fort behind them, and were answered

again from the tree line across the way, and already the silver-helmed horsemen

of Toussaint's guard were thundering down on them.

Daspir had learned to flinch at this sight.

He forced himself to keep going. Leclerc

lay foetally curled, breathless, clutching his groin, his pale face smudged with

dust. Maillart fought to control

his dancing horse. He could not see

General Lacroix anywhere. He turned

Monpoint's blade with his own as the black commander barreled past him,

thinking, Damn it! Remember all the rum

we've shared? The next rider

carried Maillart's own flag, and he thought, Riau,

Riau; it was what he had dreaded, and Riau often wore such a red rag into

battle, but the face under the tight band of the headcloth belonged to Placide

Louverture.

Maillart

was frozen. He would not strike the

boy. But Placide was riding for

Leclerc, whom Daspir had assisted first to his knees, then, unsteadily, to his

feet, as Placide rode downon him with his head floating empty under the red

cloth and his whole being poured into his right arm, the force and direction of

the blow. Daspir just managed to

get his own sword up, awkwardly angling his blade above his own head, like

raising an umbrella in a rainstorm. Placide's

falling blade snagged on Daspir's hilt, and Daspir, with his arm crooked over

his head, unbalanced by Leclerc's weight on the other side, felt the muscle tear

behind his right shoulder in the instant before Placide's horse struck him in

the back and knocked him winding into the dirt.

Look at him ride, Maillart was

thinking, imagining that Toussaint would feel the same surprised pleasure if he

could see his son now. Placide had

managed to turn his horse in an unbelievably short space, the animal's

hindquarters scrubbing the ground, then thrusting up again into the charge.

Unconsciously, Maillart spurred up Eclair.

He'd have to meet Placide this time, now Daspir had been knocked out of

the action and Leclerc stood bewildered, dust-blinded, no weapon in his empty

hands, with Placide bearing down on him, admirably singleminded on his target. As Maillart recognized that he himself would be inevitably

too slow, too late, the cavalry commander Dalton appeared from the dustcloud and

snatched Leclerc across his saddle-bow like a sack of meal (due to the nature of

his hurt, the Captain-General would be unable to bestride a horse for many

days). Placide's sword flashed

through the space where Leclerc had been a split second before, with such force

and penetration that the point hacked a divot from the ground.

Maillart

rode by. He could not wheel his

horse in twice the time it took Placide-- the boy was going to catch him from

behind. But instead Placide rode

past, ignoring Maillart, bent on Dalton as he carried Leclerc away.

All of the French were routed again.

Daspir popped up under Maillart's horse, spitting a mouthful of grit.

When Maillart caught his right arm to help him up,

Daspir's face went a stark cold white.

He managed to scramble up behind Maillart, then fainted dead away from

the pain as soon as he was seated.

To

his surprise, Maillart saw that he was overtaking Placide now.

He did not raise his weapon. It

was too difficult, when he had to hold the unconscious Daspir on by clamping the

arm wrapped around his waist. He

passed Placide. They were running,

all the French were in full flight; they would not stop before they reached the

ferry landing at the river below the town.

Placide was losing ground on them, Maillart could see over his shoulder.

Now only a splotch of the red rag was visible, now only the flag high on

its staff. Then he was gone.

At last Placide's concentration admitted the voice of Monpoint, shouting

for him to slow down, turn back. He

had too much outdistanced the rest of his squadron, and now the bay was

flagging. He drew on the reins and

walked the horse, still staring after the stampeded French army.

The only thought his mind would hold was that after all he had been

wrong, not to have changed horses.

The

two trumpeters and the drummer were windbroken and exhausted from blowing and

beating through the whole day's fighting. Gaston,

however, sat up crosslegged like a grasshopper, still bowing his fiddle through

slow, melancholy, country airs that scarcely varied one to the next.

The noise was nerve-wracking, but it did mask the screams of the men of

the Ninth, who had been turned over to Lamartinière after their capture.

Bienvenu

had passed a hard day in the fighting, and the doctor excused him from nursing

duties, that he might go to watch the tortures which were this evening's

entertainment for the troops. During

the day the doctor had got some nursing help from Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière,

when she was not occupied by sniping on the wounded French below the walls,

using a long rifle much like the doctor's, with a skill all the men applauded.

Yet when she nursed, there was a forcefulness in her calm that seemed to

make a man stop bleeding at her touch.

This

evening, however, Marie Jeanne had gone to join her husband.

Encouraged by Dessalines, himself somewhat irritated by a chest wound

he'd acquired from falling against a stake, Lamartinière was visiting the worst

punishments anyone could imagine on the men of the Ninth who'd turned their

coats to fight for French. From all

this, the doctor had averted his eye, but Descourtilz spied on the proceedings

for a little while, then crept back to the doctor's post to whisper the details:

the first was skinned alive, then they tore out his heart and drank his

blood; the second was castrated and had his guts pulled out of his belly into

the fire while he still lived; they broke all the bones of the third and then--"

"Shut

up, for Christ's sake," the doctor said.

"Be quiet and help me with these bandages."

Descourtilz

left off his narrative, and joined in the work.

They had organized a hospital shelter along the north wall of the powder

magazine. The area was easiest to protect from the sun, and if

Dessalines did blow up the fort, the end for the wounded would at least be

quick.

At

the opposite end of the fort, most of the garrison clustered around the men who

were being tortured. Lamartinière had taken a high tone, at the beginning: I

want to have the satisfaction of destroying, myself, these miserable traitors

who've served in the ranks of the French, against the liberty of their brothers. But as he moved into the work, a blood-rage transformed him;

he ceased to resemble his civilized self. The

throng of men blocked the doctor's view, though if he glanced in the direction

of the moaning, he could see the red flickering glow of the fire at the center

of the ring. The crowd expanded or

contracted, shuddered or rippled, shouting or sighing its appreciation of each

fresh extravagance of cruelty. Above

it all, the violin whined.

"How

do you turn your back on such monstrosity?" Descourtilz finally said.

"It

won't be altered by my looking at it," the doctor said.

The work was finished; he sat on the ground with his back against the

rough stone wall of the magazine. A

few stars gleamed above the shattered saplings on the hill beyond the wall. He scratched at the edge of his head wound, under the

bandage.

"In

ninety-one I was prisoner in the camps of Grande Rivière," he said.

"What I saw there was most likely beyond the imagining of anyone we

have here. And I missed being done

away with here as narrowly as you, down there in the town...." He hesitated. "In

the end I think there's no good facing it.

I know it's there. But I

don't want my mind filled with the images."

The

violin struck a sour note, then limped back into tune.

The throng around the torturers sucked up a very deep breath.

"They

are all savages," Descourtilz said bitterly.

"They

are a people of extremes," the doctor said.

At that moment he believed that he might rip someone's heart out himself

if the action would win him a drink of rum.

He felt that Descourtilz's assertion was wrong, but it was difficult to

articulate his reasons.

"When

this festivity is over," he said, "they'll be as mild as little

children, most of them."

"Not

Dessalines," said Descourtilz, and paused.

"I know what you mean-- but isn't that the most horrible thing of

all?"

"No,"

said the doctor. "No, I don't

think so."

Descourtilz

merely grunted, then stretched out on his side.

A few minutes later, Gaston left off his fiddling.

It was finished; the men were drifting away from the embers of the fire. Bienvenu came slinking along the wall toward the doctor's ajoupa,

a little abashed, like a dog that's done mischief.

"Gegne

clairin," he said, offering a gourd.

There's rum.

The

doctor took the gourd with an inexpressible gratitude.

After his first gulp he discovered his fingers had got all sticky with

blood from brushing Bienvenu's hand. Quickly

he scrubbed them off in the dirt. Bienvenu

had gone to sleep instantly, peacefully; he lay on his back and snored. The doctor took another, more contemplative swallow of rum

and weighed the gourd in the palm of his hand, guessing it to be half-full at

least. Carefully he stoppered it

and put it out of sight, in the straw bag where he kept his healing herbs.

Though

he was exhausted, he could not sleep. Maybe

it was the blood-smell steaming from Bienvenu that disturbed him.

For half an hour he twisted one way or another on his mat. At last he sat up and took one more short sip of rum, then

began walking along the wall in the direction of the gate. The stars were now brighter overhead, and he could pick out a

few constellations: the Corona Borealis, Hydra, the Crab. By the last coals of the bonfire, Dessalines and Lamartinière

sat muttering. The doctor turned

his face from them as he passed. The

rum put a distance between him and the idea that had come to him on the mat: he

was not very likely to leave this situation alive.

At

an embrasure beside the gate he stopped and looked out along the cannon barrel.

Under the rounded roof of stare he could discern some indistinct movement

among the hundreds of corpses scattered over the field.

His glasses were smudged but when he took them off to clean them they

slipped through his numb fingers, rang off the cannon barrel and went spinning

away. When he leaned out to snatch

for them he overbalanced and was falling too, whirling, nauseous... he saw the

glasses shatter against a stone. Then

he was on his feet again, suffused in the warm smell of Nanon, and Nanon was

handing him his glasses.

The

doctor blinked and caught his breath. He

steadied himself against the wall. Where

he'd thought he'd seen Nanon stood the commander Magny, looking at him with mild

interest or concern. His glasses

were in his hand, unbroken. He

polished them on the hem of his shirt and put them on.

"Dogs."

Was

it himself or Magny who had spoken, or maybe the sentry who had just joined them

from the gate? In any case the dogs

were there, great bristling, brindled casques

out of the mountains, packs of them, moving among the cadavers to feed.

"It

is not acceptable," Magny said. He

looked at the doctor, as if for confirmation, but the doctor could not draw his

eyes from the view. In the bluish

light of the icy stars, the wild dogs hunched their shoulders and lowered their

heads and jerked their jaws to loosen and gulp cold chunks of human flesh.

"We'll

put an end to this." Magny

turned and muttered something to the sentry.

Ten minutes later they were leading a sortie from the fort, to drive away

the dogs and stack the bodies between stacks of wood for burning.