From The Stone That the Builder Refused

First published in Conjunctionsn 41, Fall 2003 under the title "Two Kingdoms"

Copyright Madison Smartt Bell (c) 2004 all print rights reserved

Chapter 3

Cry

in the Dark

"You

were uneasy in the night," Michel Arnaud remarked to his wife.

"Oh?"

said Claudine Arnaud, pausing with her coffee cup in mid-air.

"I regret to have disturbed your rest."

"It

is nothing," Arnaud said. He

looked at her sidelong. The

suspended coffee cup showed no hint of a tremor.

In fact, Claudine had appeared to gain strength these last few months.

She was lean, certainly, but no longer looked frail.

Her face, once pallid, had broken out in freckles, since lately she took

no care against the sun. She sipped

from her cup and set it down precisely in the saucer, then reached across the

table to curl her fingers over his wrist.

"Don't

concern yourself," Claudine said, with a transparent smile.

"I have no trouble." Behind

her chair, the mulattress Cléo shifted her feet, staring mistrustfully down at

Arnaud, who raised his eyes to meet hers briefly.

"Encore

du café, s'il vous plaît."

Cléo

moved around the table, lifted the pot and poured.

The pot was silver, newly acquired-- lately they'd begun to replace some

of the amenities lost or destroyed when the rebel slaves burned this plantation

in 1791. Household service was

improving too, though it came wrapped in what Arnaud was wont to regard as an

excess of mutual politeness. And Cléo's

attachment to his wife was a strange thing! --though he got an indirect benefit

from it. In the old days, when Cléo

had been his mistress as well as his housekeeper, the two women had hated each

other cordially.

He

turned his palm up to give his wife's fingers a little squeeze, then disengaged

his hand and stirred sugar into his coffee.

White sugar, of his own manufacture.

There was that additional sweetness-- very few cane planters on the

Northern Plain had recovered their operations to the point of producing white

sugar rather than the less laborious brown.

Marie-Noelle

came out onto the long porch to serve a platter of bananas and fried eggs.

Arnaud helped himself generously, and covertly studied the black girl's

hips, moving deliciously under the thin cotton of her gown as she walked away.

In the old days, he'd have had her before breakfast, and never mind who

heard or knew. But now--

he felt Cléo's eyes were drilling him and looked away, from everyone; he

hardly knew where to rest his gaze.

Down

below the low hill where the big house stood, the small cabins and ajoupas

of the field-hands he'd been able to regather spread out around the tiny chapel

Claudine had insisted that he build. The

blacks were now taking their own morning nourishment and marshalling themselves

for a day in the cane plantings or at the mill; soon the iron bell would be

rung. Claudine and Arnaud were

breakfasting on the porch, for the hypothetical cool, but there was none.

The air was heavy, oppressively damp; drifts of soggy blue cloud cut off

the sun.

Arnaud

looked at his wife again, more carefully. It

was true that she appeared quite well. There

was no palsy, no mad glitter in her eye. Last

night they had made love, an uncommon thing for them, and it had been uncommonly

successful. They fell away from

each other into deep black slumber, but sometime later in the night Arnaud had

been roused by her spasmodic kicking. She

thrashed her head in a tangle of hair and out of her mouth rose a long high

silvery ululation. Then her voice

broke and went deep and rasping, as her whole body became rigid, trembling as

she uttered the words in Creole: Aba blan!

Tuyé moun-yo! Then she'd

convulsed, knees drawing to her chest, the cords of her neck all standing out

taut as speechlessly she strangled. Arnaud

had been ready to run for help, but then Claudine relaxed, went limp and

presently began to snore.

He

himself had slept but lightly for what remained of the night.

And now he thought that Cléo, who slept in the next room, beyond the

flimsiest possible partition, must have heard it all.

Down with the whites. Kill

those people!

Down

below the iron bell clanged, releasing him.

Arnaud pushed back his chair and stood.

When he bent down to peck at his wife's cheek, Claudine turned her face

upward so that he received her lips instead.

A

hummingbird whirred before a hyacinth bloom, and Claudine felt her mind go out

of her body, into the invisible blur of those wings.

She had gone down the steps from the porch to watch her husband descend

the trail to his day's work. Behind

her she heard Cléo and Marie Noelle muttering as they cleared the table.

"Té

gegne lespri nan tet li, wi...."

True

for them, and Claudine felt no resentment of the comment.

There was a spirit in her head....

She was so visited sometimes when she slept, as well as when the drums

beat in the hounfor.

To others, a spirit might bring counsel, knowledge of the future even,

but Claudine never remembered anything at all.

Unless someone perhaps could tell her what words had been uttered through

her lips-- but she would not ask Arnaud. Afterward

she normally felt clean and free, but today she was only more agitated. Perhaps it was the heavy weather. Her hands opened and closed at her hips.

She could not tell which way to turn.

At

this hour she might normally have convened the little school she operated for

the smaller children of the plantation (though Arnaud thought it a frivolity and

would have stopped it if he could). But

in the heavy atmosphere today the children would be indisposed.

And though her teaching often soothed her own disquiet, she thought today

that it would not. She turned from

the descending path and walked around the back of the house, swinging her arms

lightly to dry the dampness of her palms.

Here

another trail went zigzag up the cliff, and Claudine grew more damp and clammy

as she climbed. A turn of the trail

brought her to a flat pocket, partly sheltered by a great boulder the height of

her own shoulders. The trail ended

in this spot. She stopped to

breathe. This lassitude!

She was weary from whatever had passed in the night, the thing that she

could not recall. She waited till

her breath was even, till her pulse no longer throbbed, then, standing tip-toe,

reached across the boulder to wet her fingers in the trickle of spring water

that ran down the wrinkles of the black rock.

The water was sharply cold, a grateful shock.

She sipped a mouthful from the leaking cup of her hand, then pressed her

dampened fingertips against her throat and temples.

"M'ap

bay w dlo," a child's voice called from behind and above her.

"Kite'm fe sa!"

Claudine

settled back on her heels. In fact

the runnel of the spring was just barely within her longest reach.

Etienne, a black child probably five years old, bare-legged and clothed

only in the ragged remnant of a cotton shirt, scampered down toward her, his

whole face alight. I'll give you water-- let me do it. There was no trail where he descended, and the slope was just

a few degrees off the vertical, but a few spotted goats were grazing the scrub

there among the rocks and Etienne moved as easily as they.

He bounced down onto the level ground beside her, and immediately turned

to fish out a gourd cup that lay atop a barrel of meal in a crevice of the

cliff-- Arnaud having furnished this spot as an emergency retreat.

Grinning, Etienne scrambled to the top of the boulder and stretched the

gourd out toward the spring, careless of the sixty-foot drop on which he

teetered.

"Ai,"

Claudine gasped. "Attention,

cheri." She took hold of

his shirt-tail. But Etienne's

balance was flawless; he put no weight against her grip.

In a moment he had slipped down to the boulder and was raising the

brimming gourd to her.

"W'ap

bwe sa, wi," he said. You'll

drink this.

"Yes,"

Claudine, accepting the gourd with a certain ceremony.

The water was very cool and sweet. She

swallowed and returned the gourd to him half full and when he'd drunk his share,

she curtsied with a smile. Etienne

giggled. Claudine smoothed her

skirts and sat down on a stone, looking out.

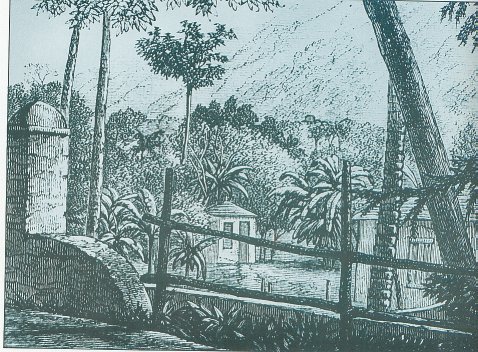

Below,

the cabins of the field-hands fanned out randomly from the little white-washed

chapel. They'd overbuilt the site

of the old grand'case which had been

burned in the risings of 1791-- the house that had been the theater of her

misery when Arnaud first brought her out to Saint Domingue from France.

More distant, two dark threads of smoke were rising from the cane mill

and distillery, and further still, two teams of men with ox-drawn wagons were

cutting and loading cane from the wide carrés

marked out by citrus hedges.

The

higher ground where Arnaud had built the new grand'case

was a better spot, less plagued by insects, more secure.

On any height, however modest, one had a better chance to catch a breeze.

Claudine realized she had hoped for a breath of wind when she climbed

here, but there was none, only the heavy air and the lowering sky, the dull

weight of anticipation. Something

was coming-- she didn't know what. She might, perhaps, ask Cléo what she had shouted in her

sleep....

A

cold touch startled her. She turned her head; the smiling Etienne was dabbling water

around the neck line of her dress. After

the first jolt the sensation was pleasant.

She felt a drop purl down the joints of her spine.

"Ou

pa apprann nou jodi-a," he said. You

are not teaching us today. A

statement, not a question.

"Non,"

said Claudine, and as she thought, "It is Saturday."

Etienne

leaned against her back, draping an arm across her shoulder.

His slack hand lay at the top of her breast, his cheek against her hair.

In the heat his warm weight might have been disagreeable, but she felt

herself wonderfully comforted.

Idly

her gaze drifted toward the west. Along

the allée which ran to the main road, about two thirds of the royal

palms still stood. The rest had

been destroyed in the insurrection, so that the whole looked like a row of

broken teeth. It seemed that the

high palms shivered slightly, though where she sat Claudine could feel no

breeze. Beyond, the green plain

curved toward the horizon and the blue haze above the sea.

Midway, a point of dust moved spiderlike in her direction.

She

shifted her position when she noticed this, and felt that Etienne's attention

had focussed too, though neither of them spoke.

They watched the dot of dust until it grew into a plume, pushing its way

toward them through the silence. Then

Claudine saw the silver flashing of the white horse in full gallop, and the

small, tight-knit figure of the leading rider. The men of his escort carried

pennants on long staves.

"Come!"

she said, jumping up from her stone. "We

must go down quickly."

It

seemed unlikely that Etienne would have recognized the horseman, but he ran down

the path ahead of her in a state of high excitement, his velocity attracting

other small children into his wake. Claudine

went more slowly, careful of the grade. As

she passed the house, Cléo came out onto the long porch, shading her eyes to

look into the west, and Marie Noelle joined her, wiping her hands on her apron.

Claudine

stopped at the edge of the compound, looking down the long allée

to the point where Arnaud had recently hung a wooden gate to the stone posts

from which the original ironwork had been torn.

She watched; for a time there was no movement.

Nearby a green shoot had sprung four feet high from the trunk of a

severed palm, and a blue butterfly hovered over its new fronds.

Etienne and the playmates he'd gathered went hurtling down the allée,

scattering a couple of goats who'd wandered there.

The children braked to a sudden halt at the skirl of a lambi

shell. Immediately the wooden gates swung inward.

Flanked by the pennants of his escort, Toussaint Louverture rode toward

her at a brisk trot, astride his great white charger, Bel Argent.

Claudine

drew herself a little straighter, and crossed her hands below her waistline.

She was conscious of how she must appear, fixed in the long perspective

of the green allée.

There was a hollow under her heels where once had been a gallows post.

She took a step forward onto surer ground, and recomposed herself for the

reception.

Spooked

by the advancing horsemen, the children turned tail and came running back toward

her. Etienne and Marie Noelle's

oldest boy Dieufait took hold of her skirts on either side and peeped out from

behind her. Toussaint had slowed

his horse to a walk several yards short of her, so as not to coat her with his

dust. He slipped down from the

saddle, and walked toward her, leading Bel Argent by the reins.

As always, she was a little surprised to see that he was no taller than

she was herself once he had dismounted. Shaking

the children free of her skirt, she curtsied to his bow.

"You

are welcome General," she said, "to Habitation Arnaud."

"Merci."

Toussaint took her hand in his oddly pressureless grip and bowed his head

over it. Claudine felt a tingle

that sprang upward from the arches of her feet-- when she'd thought herself long

immune to such a blush. There was a

pack of rumors lately, that Toussaint received the amours

of many white women of the highest standing, attracted by the thrill of his

power if they were not simply angling for gain.

He did not kiss her hand, however, but only breathed upon her knuckles,

and now he raised his eyes to meet her own. His hat was in his other hand, his head bound up in a yellow

madras cloth. The gaze was

assaying, somehow. Toussaint broke

it with a click of his tongue, as if he'd seen what he'd been looking for.

"You'll

stay the night," Claudine said. "I

trust-- I hope."

"Oh

no, madame," Toussaint told her, and covered his mouth with his long

fingers, as if it pained him to disappoint her.

"Your pardon, but we are pressed-- we stop for water only, for our

horses and ourselves."

Behind

him, Guiaou and Riau had ridden up, Guiaou still brandishing the rosy conch

shell he'd used to trumpet their arrival. Claudine

pressed her hand to the flat bone between her breasts.

"But--

tomorrow we will celebrate the Mass."

"Is

it so?" said Toussaint, smiling slightly, with the same automatic movement

to cover his mouth. "Well then. Of

course."

Claudine

fluttered at the little boys who still stood round-eyed at her back.

"Did you not hear?" she hissed at them.

"Go find something for these men to drink-- and take their horses to

water."

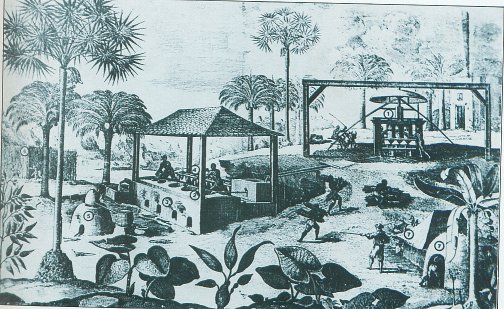

Michel

Arnaud received the news of Toussaint's arrival with mixed emotions.

The word that horsemen were on the way came to him shouted from man to

man across the cane fields, and by the time he stepped to the door of the mill

he had the comical view of tiny Dieufait leading the huge white warhorse toward

the water trough. Toussaint was

here, Arnaud thought, in part to reassure himself-- to touch the proofs that his

government had restored conditions wherein a planter might refine white sugar.

For sugar was money, and money was guns.... Arnaud chopped off that

sequence of ideas. Also of course

there was the issue of inspection, and enforcement of the new and strict labor

code for the free blacks.

Arnaud had benefited from these rules, although his workers found them

very harsh. But at any rate it was better to be inspected by Toussaint

than Dessalines. The whip had been

long since abandoned, but if Dessalines got hold of a laggard or a truant he

might order the culprit flogged with a bundle of thorny vines, which tore the

skin and laid the flesh open to infection, so that the man might afterwards die.

It was true that the others would work that much harder, for a few days

at least after Dessalines had passed. Toussaint

had a different style-- if he had not been terribly provoked, he punished only

with a glare, whereupon the suspect would apply himself to his cane knife or hoe

with tripled diligence, pursued by his own imagination of what might follow if

he did not.

But

somehow Arnaud was not eager for this meeting.

Let Claudine play hostess if she would; he knew she'd press Toussaint and

his men to dine with them that night. If

he accepted, they'd be in for a display of his famous piety on the morrow

morn.... He pulled down the brim of

the wide straw hat he wore against the sun, and walked behind the mill down the

crooked path which led through the bush to his distillery.

Arnaud did not drink strong spirits as carelessly as he once had, but it

seemed to him now advisable to test the quality of the morning run.

There,

about twenty minutes later, Toussaint came down with his companions: Captain

Riau of the Second Regiment and Guiaou, a cavalryman from Toussaint's honor

guard. At once Arnaud, bowing and

smiling, proffered a sample of his first-run rum, but the Governor-General

refused it, though he saw it dripped directly from the coil.

Riau and Guiaou accepted their measure, and drank with evident

enthusiasm.

"What

news have you from the Collège de la Marche?" Toussaint inquired.

"I

beg your pardon?" Arnaud stuttered.

Toussaint

did not bother to repeat the question. Arnaud's

brain ratcheted backward. A couple

of Cléo's sons, whom he had fathered, had indeed been recently shipped off to

that same school in France where Toussaint's brats were stabled.

They were actually Arnaud's only sons so far as he knew, as Claudine was

barren, but he had never meant to acknowledge them. He had sold all Cléo's children off the plantation when they

were quite small, but a couple of them had reappeared, a little after Cléo did.

Faced with Cléo's importuning, Arnaud had seen the wisdom of sending

those boys overseas to school-- which got them off the property at least.

In his present situation he was not able to pay the whole of their

expenses, but it seemed that Cléo had a brother who'd prospered quite

wonderfully under the new regime....

How

the devil had Toussaint known about it? He

made it his business to know many unlikely things.

At least he had not put the question in Claudine's presence; there was

that to be grateful for.

"No, no, we have heard nothing yet," he said, with rather a

sickly smile. "The boys are

remiss! -they do not write their mother."

There

the subject rested. The four of them set out on the obligatory tour: Cane fields,

provision grounds, the cane mill and refinery.... At the end, Toussaint intruded into Arnaud's books, pursing

his lips or raising his eyebrows over the figures of his exports and his income.

Claudine,

with the aid of Marie Noelle and Cléo, had organized a midday meal featuring

grilled freshwater fish, with a sauce of hot peppers, tomato and onion.

Toussaint took none of this, but only a piece of bread, a glass of water,

and an uncut mango. Arnaud knew or

at least suspected that his well-known abstemiousness was rooted in a fear of

poison. But Riau and Guiaou ate

heartily, and Riau, the more articulate of the pair, was ready enough with his

compliments. Then, finally, at the

peak of the afternoon's heat, it was time for the siesta.

The

mattress was soggy under her back. Claudine

could feel sweat pooling before the padding could absorb it.

She could not sleep, could hardly rest, tired as she felt from the night

before. The heat was still more

smothering than it had been this morning. Toussaint's arrival partly explained

her mood, she thought; it was the thing she had felt coming, but it was not yet

complete, and so her restlessness was not assuaged.

Through the slats of the jalousies she could hear Cléo's murmuring voice

as she gossiped with one of Toussaint's men on the porch.

At

her side, Arnaud released a snore. Claudine

felt a flash of resentment, that he could rest when she could not.

But he'd taken a strong measure of rum with his lunch, which was no

longer his usual practice. When he

lay down, Arnaud had taken her left hand in his and dozed off caressing, with

the ball of his thumb, the wrinkled stump of the finger where she'd once worn

her wedding ring. He did this

often, almost always, but there was nothing erotic in it, and hardly any

tenderness; it was more like the superstitious fondling of a fetish.

Now she carefully disengaged her hand, slid quietly to the edge of the

bed and stood.

Cléo

sat on the edge of a stool, in a pose which showed the graceful line of her back

as she bent her attention on Captain Riau, who stood below the porch railing,

looking up at her. "Where are you going with Papa Toussaint?" she

asked him. Claudine heard a

flirtatious lilt in her voice.

"To

Santo Domingo," Riau said. "Across

the border, at Ouanaminthe--" it seemed as if he would have continued, but

he saw Claudine in the doorway and stopped.

"Bon

soir, madame," he said, lowering his head.

"Good evening." His

military coat was very correct, despite the suffocating heat-- brass buttons all

done up in a row. As soon as he'd

spoken he turned away and began striding down the path toward the lower ground.

There was room in the grand'case

only for Toussaint himself, so Marie-Noelle had found pallets for his men in the

compound below.

Cléo

turned toward Claudine, her face a mask. That

same face with its long oval shape and its smooth olive tone, which Claudine had

once hated so desperately. The

years between had left some lighter lines around Cléo's eyes and at the corners

of her mouth, but she was still supple, still attractive, though Arnaud no

longer went to her bed. In her

frustration, Claudine stretched out her hands to her.

"What

was it shouted in my sleep last night?" she said.

Cléo's

face became a degree more closed.

"M

pa konnen," she said. I don't know.

Claudine

felt a stronger pulse of the old jealous rage.

The one face before became all the faces closed against her, yellow or

black, withholding the secrets so vital to her life.

In those old days she could not visit her anger directly upon Cléo

(Arnaud had protected the housekeeper from that) so she had worked it out on

others in her vicinity. She took a

step forward with her hands still outstretched.

"Di

mwen," she said. Tell me.

Cléo's

expression broke into an awful sadness.

"Fok

w blié sa," she said, but tenderly.

You must forget it.

She took Claudine's two hands and hers and pressed them.

Claudine felt her anger fade, her frustration melt into a simpler, pain,

more pure. It was too hot for an

embrace, but she lowered her hot forehead to touch Cléo's cooler one, then let

the colored woman go and walked down the steps.

In

the compound below, Claudine drifted toward her schoolhouse, no more than a

frame of sticks roofed over with palm leaves, which the children would replace

as needed. There were some solidly

made peg benches, and a rough lectern Arnaud had ordered built as a gift to her.

This afternoon, four of the benches had been shoved together to make room

for two mats on the dirt floor. Guiaou

lay on one of these, breathing heavily in sleep, and Riau on the other, his

uniform coat neatly folded on the bench beside him.

His eyes were lidded but Claudine did not think he was really asleep; she

thought he was aware of her presence, though he did not show it.

She could see her own spare reflection warped in the curve of the silver

helmet he'd set underneath the bench.

Pursued

by Etienne, Dieufait ran by outside, rolling a wooden hoop with a stick.

The two children disappeared among the clay-walled cases.

Grazing her fingertips over the lectern, Claudine left the shade of the

school roof and walked toward the chapel. En

route she passed the little case

inhabited by Moustique and Marie-Noelle. The

cloth that closed the doorway was gathered with a string, and glancing past its

edges, Claudine saw Moustique's ivory feet hanging off the edge of the mat where

he lay. Marie-Noelle was on her

side, turned toward him and between them their new baby lay curled and quietly

sleeping.

Envy

pricked at Claudine again as she went into the chapel.

There was no door, properly speaking, but close-hung bead strings in

place of one whole wall, which could be pulled back to open a view of the altar

to the compound outside. The

interior space was very small, built on the same plan as a dog-shed that had

once stood there. The walls were

whitewashed, and eight pegged benches like those in the school were arranged in

a double row. Claudine sat down on

the farthest bench from the altar-- no more than an ordinary wooden table. Above it hung a crucifix carved in mahogany from the fevered

imagination of one of the Africans of the plantation-- or maybe it was drawn

from life, for certainly there had been horrors enough, in the last ten years of

war, to inspire such a grotesquerie as he had made.

Claudine

sat still, her back rigorously straight, hands folded in her lap.

The bead curtain hung motionless behind her, and on the roof the heat

bore down. She could not pray or

think or breathe. That drumbeat she

almost thought she heard was only the pulse in the back of her neck, a headache

rising; it would not move the spirit through her.

After

a long time, the bead curtains rustled and Toussaint Louverture walked into the

chapel. Claudine registered his

presence without quite turning her head. Reciprocally,

Toussaint displayed no consciousness of her.

He walked slowly between the two rows of benches, stopped before the

altar, and stood looking up at Christ's carved wounds.

After some time he crossed himself and sat down on the first bench, to

the left of the cross. Reaching

both hands to the back of his head, he undid the knot of his yellow madras,

which he spent some time folding into a small triangular packet.

Claudine had not seen him completely uncovered before.

The dome of his head was high and long, the black skin gleaming on the

crown. He gave his folded headcloth

a couple of firm pats with his right palm, as if he meant to secure it to the

bench, then joined his hands and bowed his head to pray.

As

time passed the light seemed to grow dimmer.

Claudine did not know if the clouds were thickening outside or if it were

only an effect of her own fatigue. She

watched Toussaint, whose right hand slowly clicked through the beads of a

curiously carved wooden rosary. A

movement of the damp air stirred the strings of the curtain behind her, and she

felt a current lifting toward the roof, where the eaves had been left open for

ventilation.

Finally

Toussaint had concluded his prayer. He

stood up, gathering his folded headcloth in the hand that held the rosary.

When he turned toward Claudine he enacted a startle of surprise.

"O,"

he said. "Madame Arnaud."

"Monsieur

le général." She made a

slight movement as if she would rise. A

gesture of Toussaint's palm restored her to her seat. She watched him walking slowly toward her.

His head was outsized for the wiry, jockey's body-- the great orb of his

skull counterbalanced by the long, jutting lower jaw.

The body, whose meagerness was accentuated by the tight riding breeches

he wore, carried its burden of head with a concentrated grace that rid

Toussaint's whole aspect of any comical quality.

He took a seat across the dirt-floored aisle from her, swinging a leg

across the bench to straddle it like a saddle.

"It

is good to see our Catholic religion so well observed here," he said,

"when so often it is neglected elsewhere, among the plantations."

Claudine

inclined her head without speaking.

"I

have catechised some of the children walking the grounds this afternoon,"

he told her. "I find them to

be well instructed. The boy Dieufait, for example, recites the entire Apostolic

Creed with perfect confidence."

"As

well might be expected of the son of a priest."

Claudine attempted an ambiguous smile, in case Toussaint were moved to

find irony in what she had said.

"They

say that you give them other instruction too," Toussaint said.

"That you teach them their letters as well as their catechism.

This afternoon I passed by your school-- of which one hears talk as far

away as Le Cap, if not farther."

"Is

it so?"

"Why,

yes," Toussaint said. "You

are notorious."

Claudine

felt a bump of her heart. Behind

her the strings of the curtain shivered; outside a wind was rising.

She was notorious for a great deal more than her little school, and

Toussaint must know something of that, though she wasn't sure how much.

"You

rather alarm me," she said.

"There

is no need, madame," Toussaint said. "Of

course not every comment is favorable, as there are always some who believe that

the children of Guinée must be held in the ignorance of oxen and mules."

Claudine

lowered her head above here lap. One

of her feet had risen to the ball, and the whole leg was shaking; she couldn't

seem to make it stop.

"Yes,"

Toussaint said. "My parrain,

Jean-Baptiste, taught me my letters when I was a child on the lands of the Comte

de Noé."

Claudine

raised her head to look at him. He

was telling her the true version of the story, she thought, which was unusual.

Of late he had been circulating a tale that he had been taught to read

and write just before the first rebellion, when he was already past his fiftieth

year.

"If

not for that," Toussaint said, "I should have remained in

slavery."

"And

many others also," Claudine said.

"It

is so." Toussaint squeezed the

bench with his thighs, as if it really were a horse he meant to urge on.

"But your husband, madame. What

view does he take of your teaching?"

"He

indulges it." Claudine lowered her head.

"Does

he not find himself well-placed today, Monsieur Arnaud?"

Toussaint seemed to be asking the question of a larger audience than was

actually present; his voice had become a little louder.

"With the restoration of his goods, the men back working in the

fields. Why, a fieldhand may learn

to read a book and be no less faithful to his hoe. Does he not find it to be true?"

"I

hope so," Claudine said. "I

believe so... yes, I mostly do."

"You

may not be aware that your husband conspired long ago in a royalist plot against

the Revolutionary government here," Toussaint said.

"Or then again, perhaps you know it.

Those men engaged to start a false rising of the slaves in ninety-one--

thinking to frighten the Jacobins with a spectacle of the likely outcome of

their own beliefs. They thought

they could control a slave rising, those conspirators, but as you see they were

quite wrong. He was one of them,

Michel Arnaud, with the Sieur de Maltrot, and Bayon de Libertat my former

master, and Governor Blanchelande himself, who later lost his head for it, to

the guillotine in France."

"As

did so many others," Claudine murmured.

As she spoke, her eye fell on the rosary, which Toussaint held in one

hand against the yellow headcloth, and she saw for the first time that each of

the small wooden beads was an intricately rendered human skull.

"What

an extraordinary article," she said. It

seemed her that each carved skull was just a little different from all the

others.

"It

came to me as a spoil of war," Toussaint said, and put the rosary into his

pocket, without telling her what other thing it might have come to mean to him

now.

Outside

she heard voices, the clucking of chickens as they scuttled for shelter.

The wind rose further, as the air grew chill with the coming rain.

"Ah

well," said Toussaint. "We

have our dead."

All

at once Claudine's leg stopped trembling and her raised foot relaxed against the

floor. How intimately she had her

dead! She wondered if Toussaint was

similarly placed, sometimes, or always. It

was certain that he'd caused the deaths of many more than the considerable

number he'd ushered out of the world with his own hands.

"Yes,"

she burst out. "My husband killed many before the risings, he killed

the children of Guinée with no more regard than for ants or for flies, and with

torture sometimes, as bad as that--" she

flung out her arm toward the crucifix. "Yes, this morning you rode your horse through the place

where there once stood a pole, and to that pole husband used to nail his

victims, to die slowly as they hung-- like that--"

Her rigid fingers thrust toward the cross again.

"And there was worse, still worse than that. No doubt you know it--

he was famous for it all." Her

whole arm dropped, and she felt her face twisting, that alien sensation as she

moved a step farther away from her body. The

blood beat heavy in her temples, and she heard the other voice beginning to come

out from behind her head. "Four hundred years of abominations -- four hundred years for all to

endure, and his no larger than a grain among them--"

She

stopped the voice, and came back to herself-- she wanted now to remain herself.

Toussaint had leaned back a little away from her and regarded her with

his chin cupped in one hand.

"During

the risings my husband suffered very much," Claudine said.

"For a time he was made clean by suffering, as fire will burn

corruption from the bone. Oh, he

has still cruelty in his nature, and avarice, and too much pride, with contempt

for others, white or black, but now he fights against it.

I see him fight it every day."

Her

voice cracked from hoarseness; her throat felt very dry.

"And

yourself, madame?"

She

took it for an answer to the prayer she could not voice.

With a lurch she dropped to her knees on the space of packed dirt between

them, embraced his legs and pushed her face into his lap.

"Hear

my confession," she said, but her voice was too muffled to be understood.

Toussaint was pushing her back by the shoulders.

"Madame,

Madame," he said. "Control

your feeling."

"No,"

Claudine said. "No-- I want to touch you not in the flesh but in the

spirit." But she had grasped

his wrists now, to hold his hands firm against her collarbones.

"Hear

my confession," she said, clearly now.

"I

am no priest," Toussaint informed her.

He twisted his hands free and drew them back.

"You have your own priest here, who must confess you."

Claudine's

arms dropped slack to her sides. To

her surprise, he reached for her again, wrapping both hands around her head,

balancing it on the point where his fingertips joined in the deepest hollow at

the back of her neck.

"It

is not easy to enter into the spiritual life," he said.

By the soft and absent tone of his voice he might have been talking to

himself. But he was looking into

her head as if it were transparent to him.

"So

you have been walking to the drum, my child," he said.

"Sometimes there is a spirit who dances in your head."

The

release of his hands let go a flash of light behind her eyes.

The wind had blown the bead strings apart and was stirring the dust under

the benches around them.

Toussaint

cocked his head. "Lapli k'ap vini,"

he said. The rain is coming.

"Yes,

you are right," Claudine murmured. "We

must go up before we are caught here."

Outside,

the sky bulged purple over them, and above the mountains a wire of silent

lightning glowed and vanished. Toussaint

turned his head to the wind, letting his yellow madras flag out from his hand,

then caught it up and bound it over his forehead and temples and knotted it

carefully at the back before he followed Claudine, hastening to the grand'case,

reaching the shelter of the porch's overhang in the seconds before the deluge

came down.

Because

Toussaint had stated, over dinner, his need for an early departure, the Mass

commenced exactly at first light. The

hour was painfully early for some, and fewer of the plantation's inhabitants

turned out for it than might have otherwise, but still there was a respectable

crowd for Moustique to part when, with a slow and solemn step, he carried the

wooden processional cross into the little chapel.

Behind him the children of Claudine's school marched, singing, Wi,

wi, wi, nou se Legliz, Legliz se nou....

Claudine took her seat in the front row, next to the yawning Arnaud,

irritable with his too-early rising. Yes,

yes, yes, the Church is us, we are the Church....

Toussaint, the guest of honor, sat Arnaud's right hand, while Riau and

Guiaou shared the opposite bench with Cléo and Marie-Noelle.

The other benches were filled with commandeurs

and skilled men from the cane mill or distillery and other persons of a similar

importance. The bead curtain had

been tied up above the eaves, so the whole wall was open to the larger

congregaton outside, whose members sat crosslegged on the ground as soon as the

signal was given.

Claudine

paid small attention to the words of Moustique's sermon; her mind was utterly

fixed on the cross. Ah well, she

thought, we have our dead....

As she stared, she perceived that it was the vertical bar of the cross

which pierced the membrane between the world of the living and the world of the

dead, and allowed the spirits to rise.

Now

Moustique was chanting the Sanctus in Latin, his voice high and whining.

Above the altar, the dark crucifix ran and blurred before Claudine's

weary eyes, till it became another image. She

saw the body of her bossale maid

Mouche, who'd been lashed quite near to that very same spot in the days when a

dog-shed stood on the chapel's site, and saw again the flash of the razor in her

own hand as it slashed out the child Arnaud had planted in Mouche's womb and let

the ftus spill on the dirt of the floor, then cut so viciously at the black

girl's throat that it uncorked her blood like a fountain. And now, as Moustique presented the host, the children sang,

"Se Jezi Kri ki limyè ki klere kè

nou tout. Li disparèt fènwa pou'l

mete klète...."

The

chapel was opened to the east, so that when the rising sun cleared the mountains

it struck the whole interior with such force that everything before Claudine's

eyes was obliterated in the blaze. But

the bread had been torn, the wine consecrated.

She groped her way forward and knelt to receive.

It is Jesus Christ who is the light that illuminates all our hearts.

He drives out the darkness to put light in its place....

A

fringe of cloud drifted over the sun, dimming the interior enough for Claudine

to see more plainly. Toussaint, hands clasped before him, opened his mouth for the

descending Host as meekly as a baby bird. Claudine's

turn followed. Moustique served

Arnaud, Riau and Guiaou and the other two women, then began his second circuit

with the chalice made from a carefully trained and hollowed gourd.

Claudine held the body of Christ on her tongue.

She had confessed her crime many times and to more than one priest, but

still the chalice, when raised to her lips, returned to her the salt taste of

blood.