The

Image of Toussaint

This passage is as subtle as it is splendid (the deft insertion of Toussaint into the peerage of the great white national heroes of his time is accomplished almost by sleight of hand); at the same time, like much of the most inspired political rhetoric, it is no better than half-true. Toussaint left a considerable written record (though Phillips likely knew nothing of it): not only a copious correspondence but also the memoir he drafted in the Fort de Joux... Moreover, he has been described, from his own time into ours, by friends and admirers as often as by foes and detractors. Yet Phillips is right enough to say that practically all first-hand reports on Toussaint come from the white, European milieu; precious few comments from his black and colored contemporaries have survived. It’s also true that very few accounts of Toussaint’s life and work have been nonpartisan. He is almost always depicted—exclusively—as a devil or a saint.

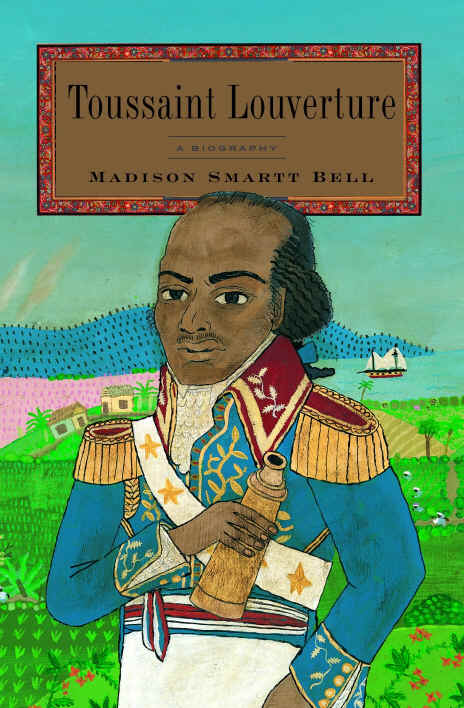

Portraits of Toussaint from his own time are reminiscent of drawings of American buffalo by European artists working from descriptions and without ever having seen a buffalo. Many of these images seem to be no more than sketches of generic African features—sometimes exaggerated into grotesque caricature. A study by Haitian scholar Fritz Daguillard suggests that two of the early portraits are at least reasonably faithful to their subject. The first, a full profile view of the black general, was probably done from life as a watercolor by Nicolas Eustache Maurin. Later rendered as an engraving by Delpech, this portrait became a model for many later artists who transported the basic image of Toussaint’s profile into various other contexts. Toussaint liked the original well enough to present it as a gift to the French agent Roume, whose family preserved it for centuries afterward. He wears full dress uniform for the occasion: a general’s bicorne hat, decorated with red and white feathers and the red, white and blue French Revolutionary cockade, a high tight neck-cloth and a high-collared uniform coat, heavy with gold braid. The features in this image agree with eye-witness descriptions of the time: Toussaint is just slightly pop-eyed, his profile marked by a prominent, under-slung lower jaw.

The second portrait, a three-quarter view, was singled out by Toussaint’s son Isaac as the only image in which he found his father recognizable. At a glance this second portrait (by M. de Montfayon, who had served under the black general as an engineer) does not look much like the first. Toussaint wears a similar coat as in the Maurin portrait, with gold braid, his general’s epaulettes, his right hand clasping a spyglass against a ceremonial sash. In this image he is bareheaded, his remaining hair gathered in a queue at the back, and we see that his forehead is very high, and his cranium remarkably large. In the Montfayon image, Toussaint’s features look more delicate, less typically African, than in the other; perhaps they were slightly idealized by the artist. If Montfayon makes the jaw less prominent, the difference can be accounted for by the angle of view. The more one looks at the two portraits together, the more reasonable it seems that they represent the same person, though in two different frames of mind. The full profile suggests a head-on belligerence; the three-quarter view presents a wary, intelligent observer. History has shown that Toussaint Louverture possessed both of these qualities, in abundance.

Twentieth century biographer Pierre Pluchon declares that “Toussaint was in no way a handsome man. On the contrary, his physique was graceless and puny.”[ii] To be sure, Pluchon is one of Toussaint’s demonizers, but even the friendly observers agree that Louverture was, well, funny-looking, though by the time his name became known, most people had learned not to laugh at him. He was short and slight, with a head disproportionately large for the body. Most descriptions report him to have been bowlegged, and in general he seems to have had a jockey’s build—and was indeed a famous horseman. His physical capacities, even when he was in his fifties (an ancient age for a slave in a French sugar colony), were very far from “puny.” According to the French general Pamphile de Lacroix, who knew Toussaint late in his career, “His body of iron received its vigor only from the tempering of his soul, and being master of his soul, he became master of his body.” [iii]

The contradictory reports on Toussaint prepared for the French home government by General Kerverseau (his dedicated enemy) and by Colonel Vincent (his determined friend) represent a polarization of opinion that has endured for two centuries since. In 1802, as Napoleon prepared the military expedition intended to repress the slave rebellion in Saint Domingue and put its leader in his place, a couple of propaganda pamphlets were published by Dubroca and by Cousin d’Avallon, who denounced Toussaint in much the same style as Kerverseau had done: “All his acts are covered by a veil of hypocrisy so profound that, although his whole life is a story of perfidy and betrayal, he still has the art to deceive anyone who approaches him about the purity of his sentiments…. His character is a terrible mélange of fanaticism and atrocious penchants; he passes coolly from the altar to carnage, and from prayer into dark schemes of perfidy…. For the rest, all his shell of devoutness is nothing but a mask he thought necessary to cover up the depraved sentiments of his heart, to command with a greater success the blind credulity of the Blacks…. There is no doubt that with the high idea which the Blacks have of him, seconded by the priests who surround him, he has managed to make himself be seen as one inspired, and to order the worst crimes in the name of heaven…. He has abused the confidence of his first benefactors, he has betrayed the Spanish, England, France under the government of kings, Republican France, his own blood, his fatherland, and the religion which he pretends to respect: such is the portrait of Toussaint Louverture, whose life will be a striking example of the crimes to which ambition may lead, when honesty, education and honor fail to control its excesses.” [iv]

Wendell Phillips was referring to writers like these when he said that Toussaint’s story had only been told by his enemies; and yet the black general’s adulators were as numerous. After his overthrow by Napoleon, his imprisonment in the French Alps inspired a sonnet by William Wordsworth:

Toussaint, the most unhappy Man of Men!

Whether the whistling Rustic tend his plough

Within thy hearing, or thy head be now

Pillowed in some deep dungeon’s earless den—

O miserable Chieftain! Where and when

Wilt thou find patience? Yet die not, do thou

Wear rather in thy bonds a cheerful brow;

Though fallen Thyself, never to rise again,

Live and take comfort. Thou has left behind

Powers that will work for thee; air, earth and skie;

There’s not a breathing of the common wind

That will forget thee; thou has great allies;

Thy friends are exultations, agonies,

And love, and Man’s unconquerable mind.

Not for nothing was Wordsworth called “Romantic.” Meanwhile Alphonse de Lamartine, as illustrious a poet in the French tradition as Wordsworth in the English, celebrated and reinforced the legend of Toussaint with a verse play named after its hero. Produced for the first time in 1850, just two years after France had permanently abolished the slavery which Napoleon had restored in 1802, the play was quite popular with the public; the critical response, however, revealed reactionary attitudes. Charles Bercelièvre gave his review the sarcastic title: “Blacks are more worthy than whites.”

“Can one believe,” he went on to say, “that in the nineteenth century, in a country that speaks of nothing but its nationalism and its patriotism, a man would be bold enough to present, in a French theater, a black tragi-comedy in which our compatriots are treated as cowards, as despots, as scoundrels, as thieves, and called by other more or less gracious epithets; in which one hears at every moment: Death to the French! Shame on the French! Do let’s massacre the French! …That Toussaint Louverture should have success among negroes—we understand that much without difficulty, but that this anti-national, anti-patriotic work, fruit of an insane, sick brain, should be produced and accepted on a French stage—that we will never understand.” [v]

From this inflamed passage it is very plain not only that the violent loss of Saint Domingue to its former slaves remained a very sore spot in France, even a half-century after the fact, but also that despite the final end of slavery in French possessions, the assumption of black racial inferiority, which the ideology of slavery very much required, had scarcely been weakened among Frenchmen. With this play, Lamartine made an argument for the equality of the races which anticipated the black pride movements of the Caribbean basin by nearly a hundred years. He offended his contemporary critics by providing his Toussaint with linguistic powers and a rhetorical style that would have been natural to a white French hero of the theater. From the modern point of view, it seems impossible that Toussaint could be made to speak in elegant Alexandrian rhyming couplets without a very great distortion of his personality, his thought, and his actual mode of expression—yet Lamartine is sometimes ingenious in adapting statements Toussaint was known to have made to the very rigid requirements of the verse form:

Ma double autorité tient

tout en équilibre:[1]

Gouverneur pour le blanc, Spartacus pour le libre,

Tout cède et réussit sous mon règne incertain,

Je demeure indécis ainsi que le destin,

Sûr que la liberté, germant sur ces ruines

Enfonce en attendant d’immortelles racines.[vi]

The Haitan people, as they named themselves, were the first to put an end to slavery in the New World, with their definitive defeat of the French in 1803 and their declaration of independence in 1804. In the course of the next half-century, the “peculiar institution” died, by slow and miserable degrees or in great spasms of violence, the last of which was the American Civil War. The story of Toussaint Louverture was adopted by the eighteenth-century abolitionists, not only Wendell Phillips but also Englishmen like M.D. Stephens and James Beard, and Frenchmen including Lamartine, Victor Schoelcher and Gragnon Lacoste, who burnished and enshrined it into legend.

Since Phillips was not constrained by a verse form or by tight theatrical unities, his Toussaint is somewhat truer to life than Lamartine’s, though the American orator permits himself many small distortions of fact, and embraces apocryphal details most warmly. For Phillips, as for Lamartine, the career of Toussaint was proof of the argument—counterintuitive in 1861 as it was in 1850—that black men were as good as white:

Now, blue-eyed Saxons, proud of your race, go back with me to the commencement of the century, and select what statesman you please. Let him be either European or American; let him have a brain the result of six generations of culture; let him have the ripest training of university routine; let him add to it the better education of practical life, crown his temples with the silver of seventy years; and show me the man of Saxon Lineage for whom his most sanguine admirer will wreathe a laurel rich as embittered foes have placed on the brow of this negro—rare military skill, profound knowledge of human nature, content to blot out all party distinctions, and trust a state to the blood of its sons-- …this is the record which the history of rival states makes up for this inspired black of St. Domingo. [vii]

When he generalized the concept, Philips grew more stark. “Some doubt the courage of the negro. Go to Hayti, and stand on those fifty thousand graves of the best soldiers France ever had, and ask them what they think of the negro’s sword.”[viii]

Emerging from the success of the Haitian Revolution, the gens de couleur, few in number as they were, enjoyed significant advantages of wealth and education over the vast black majority. The first Haitian historians—Beaubrun Ardouin, Céligny Ardouin, Saint Rémy, Thomas Madiou—came from this class, as did Toussaint’s first Haitian biographer, Pauléus Sannon, who served as Haiti’s Foreign Minister during the World War I era. The colored historians who wrote in the early nineteenth century had a rather ambivalent attitude toward Toussaint, whose army had won a fairly well-deserved reputation for brutality during a vicious civil war which pitted the newly freed blacks against the gens de couleur and which ended in 1800 with the colored party being crushed. Though Toussaint’s importance to the overthrow of slavery and the independence of Haiti was incontestable, Madiou and the other mulâtre historians could hardly help seeing him, and portraying him, as an oppressor of their tribe; Sannon, with a century’s distance on the events, described the black general with a greater objectivity and with less strangled rancor.

In the twentieth century, the story of Toussaint was taken up by the writers of négritude: a pan-Caribbean movement of black cultural pride. The Martiniquais writer, Edouard Glissant, who hails from another former French sugar colony, wrote a play called Monsieur Toussaint, which situates the black general in a newly evolving Caribbean literary tradition rather more securely than Lamartine had managed to locate him in the French. Aimé Césaire, best known for his poetry, wrote a book which is part biography, part political analysis, mythologizing Toussaint in a somewhat different way—as the first person to embody a solution to the problem of colonialism. The Black Jacobins, by a historian from Trinidad, C.L.R James, was until recently the standard work on the Haitian Revolution; James, writing in the late nineteen-thirties, has the attitudes of a fairly dogmatic Marxist, yet the avowed Marxist disbelief in the power of “extraordinary men” to influence history simply evaporates in James’s portrait of Toussaint Louverture.

The Duvalier dynasty in Haiti, which lasted from 1957 to 1986 as the most stable and also the most thoroughly repressive government Haiti has known since independence, associated itself with another Revolutionary hero, General Jean-Jacques Dessalines, fully as important an historical figure as Toussaint, but generally seen as much more violently authoritarian. When Jean Bertrand Aristide came to Haiti’s Presidency in 1990, on the crest of a wave of democratizing populism that many Haitians called the “Second Revolution,” he seemed to want to identify himself with the more conciliatory figure of Toussaint Louverture. In the beginning, the implied Aristide-Louverture comparison was subliminally subtle, but during the Haitian Revolution’s Bicentennial year of 2004, when Aristide was forced from office and the country by a United States-assisted coup d’état, he quoted—verbatim—the words Toussaint had famously spoken when was arrested and deported by the French in 1802.

For two centuries, historians, biographers, playwrights, novelists and even politicians have constructed whatever Toussaint Louverture they require—and almost always it is an extreme Toussaint: either a vicious, duplicitous, Machiavellian figure who not only destroyed France’s richest colony in an (inevitable) regression to African savagery but also laid the foundation of the most authoritarian and repressive elements in the Haitian state which came after him, or a military and political genius, autodidact and self-made man, a wise and good humanitarian who not only led his people to freedom but also envisioned and briefly created a society based on racial harmony, at least two hundred years ahead of its time. The latter figure is found in twentieth-century English biographies by Ralph Korngold and Wenda Parkinson, who, like Colonel Vincent two centuries previously, admire, defend and advocate Toussaint. By the usual extreme contrast, the oft-revised and updated biography by the French scholar Pierre Pluchon, while almost certainly the best-documented work of its kind, seems to take its attitude toward Toussaint unadulterated from the hostile, cynical report of General Kerverseau.

To pierce this cloud of contradictions one would like to return to the man himself, but it is difficult to do. Famously elusive in real life, Toussaint Louverture is no less elusive to the historian and biographer. The fictionalizing of his character is aided by the fact that during the first fifty years of his life, Toussaint walked so very softly that he left next to no visible tracks at all.

[1] My double authority holds everything in balance:

Governor for the white, Spartacus for the freedman,

All succeeds or collapse in my uncertain reign,

Sure that liberty, seeding itself in these ruins

Furrows, while waiting, its immortal roots.

[i] Phillips, p. 33

[ii]

Pluchon, (T-L, un révolutionaire noir…)

p. 59

[iii]

Lacroix 243

[iv]

Pluchon, (T-L, un révolutionaire noir…)

471-2

[v] Lamartine, Alphonse de, Toussaint Louverture, Léon François, ed. (Exeter : University of Exeter Press, 1998) p. xxvii

[vi]

Lamartine p. 35

[vii] Phillips p 42

[viii] Phillips p. 54