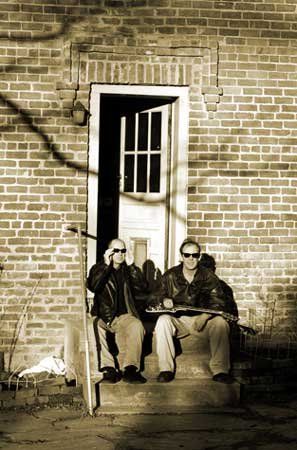

Forty Words For Fear

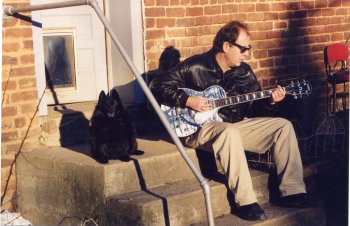

lyrics by Wyn Cooper (left, on Clavioline)

music by Madison Smartt Bell (right, Les Paul)

Rough Mix: Room Full of Tears with Forty Words for Fear.mp3

photo by Abigail Seymour Photography no use without permission |

|

Anything

Goes

When novelist Madison Smartt Bell gets together for five days with North

Carolina rock legends Don Dixon

and Mitch Easter to make a record, the results

are inspiring.

GIVE A LISTEN

To hear the results of the collaboration, go to the Gaff Music Web site – http://www.gaffmusic.com/–

to listen to cuts of Anything Goes and two other songs recorded last

month.

|

from: The Independent Weekly

KERNERSVILLE –

Something happened late on the third night of a recording session last month

in a studio just off Main Street that showed how sometimes, if you mix together

enough creative energy, talent and experience, and shake it up in fresh ways,

you might get lucky and surprise even yourself.

This was no conventional project: Acclaimed novelist Madison Smartt Bell and

poet Wyn Cooper joined North Carolina rock legend Don Dixon (producer and

bassist) and a crew of top-drawer musicians to make a record out of songs Bell

and Cooper wrote together, half on a lark, for Bell's novel Anything Goes.

Just to make it all really strange, Bell was on lead vocals (and rhythm

guitar). Cooper, who wrote the words to the songs, kicked in with readings of

some of his poetry, funked-up so it fit in with the mood of the record, dark and

weird and bluesy with song titles like "40 Words for Fear" and

"Room Full of Tears" and "The Girl in the Black Raincoat."

"I would just love for this record to be a part of some sort of overall movement of a return of art in pop music," said Mitch Easter, who hosted the five-day sessions in the sleek, million-dollar studio he and Shalini Chatterjee built in their back yard. "The word pop has become synonymous with possibly the worst music ever made, but what I see pop music as is just non-high-brow music, which means a vast array of culture for everybody."

Left alone

That third night when everything came together, Dixon took a few hours off to

head to his daughter's dance recital a county or two away, and it was like a

rainy day at grade school when the substitute teacher heads to the lounge for a

smoke and all hell breaks loose. Easter and the others did not let loose with

any paper airplanes, or electrocute any cats, or fill any chalkboards with

spectacularly obscene limericks. They just grinned as if they had.

You almost had to think Dixon had it all planned. Three decades have passed

since he burst onto the scene as bassist and vocalist of the Chapel Hill band

"Arrogance," and if Dixon knows enough to be bored by fame, he also

knows enough to remember that feeling of breaking through with something. He has

the itch to do it again. You can see it in his eyes, in his quiet, thoughtful

smiles and in the way he almost hops in his chair when he pops open the pull tab

on yet another of his fizzy musical ideas.

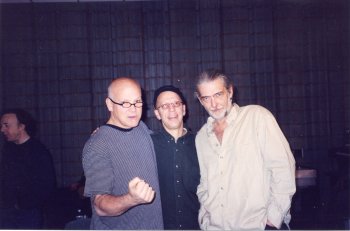

Dixon, fez

"You're not worried about whether someone's grandmother is going to put

this on at their wedding reception," he said one day during the sessions.

"You care about whether someone is going to put this on and pick up the

headphones and really listen. It only has to be a few people. Anybody who writes

poetry in the face of no one giving a rat's ass knows what I'm talking about.

"The appeal of working on this is you have two smart guys who have a lot

of ideas and have created these things, and now we just have to figure out how

to make this work. The groove and feel side of music is not necessarily an

intellectual process, but to create these things you have to create an

environment where you have those levels."

Sometimes that means ducking out, which felt in a way like it was one more

mad Dixon scheme to channel the creative process. Before he hit the road to

watch his daughter, he urged the crew to carry on without him. Maybe, he

suggested in an offhand whisper, they could do something to jazz up Cooper's

spoken-word contributions.

Cooper also wrote the words to a poem called "Fun," which became a

song called "All I Wanna Do," which became Sheryl Crow's breakthrough

hit. He was no stranger to the music business (and that earned him respect) but

his voice was. No one was going to say anything, but Cooper sounds like a poet.

He enunciates. His voice rings. It rises and falls. But it does not rock. If, as

Sonny Boy Williamson once said, the blues are something you come in con-TACT

with, this was a voice that needed to broaden its experience.

No problem. The boys were there to help. They soaked up some enchiladas and

beer down the road in the smoke-friendly rear room of a Mexican restaurant that

had stocked up on fluorescent lights bright enough to zap even the hardiest

insect, Star Wars-style, then got down to some serious noodling.

Before you knew it, percussionist Jim

Brock, the linchpin to everything that

happened that week, was stretching out like an aerobics instructor. It was quite

a sight, considering Brock was the tallest of the bunch, at a little over

6-foot-2, and usually sat meditatively behind his drum kit, dreaming up

something just off-kilter enough to ring Dixon's bell, or folded his long limbs

into a comfortable pose on the big sofa in the control room.

But now Brock was playing the short wave. He fiddled and fussed with the

knobs until he found just the right shard of static-fringed noise, coming out of

the night like a hyena call. Now, to make music, he was using his body as an

antenna, extending then contracting, extending then contracting, and in the

control room, Easter and the others shook their heads with pleasure.

photo by Abigail Seymour Photography no use without permission

Dreamy and weird

There was no need to talk about how right the sound was. Something dreamy and

weird and edgy was taking shape, and everyone knew it. This was even more fun

than the day before, when Brock had tapped out a rhythm on the spiral metal

staircase rising out of the back of the studio, using nothing but his hands.

"When you do this all the time, and you've done it for years, a lot of

it gets kind of nuts and bolts for you," said Brock, also co-producer.

"Then people come in who don't do it all the time, nonprofessionals, and

they still have that sparkle that you used to have, like I had when I was a kid.

"I still have that love and everything, but time has kind of smoothed

the edges out. You see that gleam of excitement in their eyes, and you kind of

feed off of that a little bit. It's the same thing when I play the stairs.

That's a whole new thing. It's still music, and I'm still doing what I do. But

it's fresh. I've created something that wasn't out of something that is

different."

But was this too out there? Was the radio and the other effects too pulsing,

too reverbed, too weird? Maybe--but so what?

Easter, Dixon, Frank, Brock

"I think we owe it to ourselves to preserve this little piece of found

art," Easter said, hands on the console as always.

What else did the cut need? How about a banjo solo?

Chris Frank was only too

happy to oblige. He'd already had a tuba solo, the day before, and a trombone

solo and, oh yes, played the accordion and the ukulele. He'd played the electric

piano and the upright piano and the Hammond B-3 organ. Dixon rides Frank harder

than Brock or Easter, and has a way of squeezing everything he can out of him.

But not then. Not that night. Dixon was gone, and this was about Frank having

fun. As soon as Easter assured him they weren't kidding, he really got to play

"Sweet Sue," he ran off to get his banjo, wasting no time.

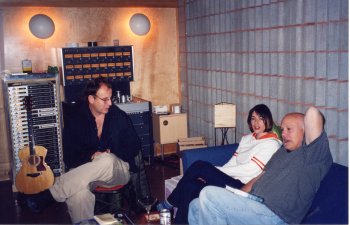

Bell, Frank

Scott Beal slid out of his chair and was lying flat on his back, laughing so

hard his health seemed in danger. If anyone could laugh, it was Beal, a cross

between original Grateful Dead singer Pig Pen McKernan and Animal House-era

John Belushi. Beal was the one paying the bills. He was the one making this

happen. He was the one with the record label, Gaff Music, designed for just such

projects as this, a quirky mix of musical talent and the life knowledge and

soulfulness of an old-school, get-out-there-and-live novelist like Bell.

Late-night music for late-night people, Beal called it later, once he heard the

final mix, and it's hard to argue with that.

"It was great fun," Easter said later. "It's really great when

you've been listening to normal instruments, and you have to be concerned about

being in tune, and singing the right words, and your timing and all that, and

then you shift gears and you want it to sound as destroyed and wrong as

possible. That's a great relief after a while. It's nice to have an evening like

that thrown in."

This banjo solo was no runaway train. Oh no. Easter brought it in and out

like a radio signal fading in and out on a late-night drive across the

heartland. It was there, and then it wasn't, and when it was gone you wondered

if you had actually heard it or if your own overactive imagination had somehow

conjured it out of nothing. That was the idea, of course. And it worked.

"What are we going to do after we grow up?" Frank called out to no one in particular, back in the control room.

Dark places

Easter had a Christmas-morning grin as he sat and listened at the big console

he imported from Britain once the BBC gave up on it. It's a famous model, one of

only a few around, and Easter could work it even when he was nonchalantly

knocking off a crackling little guitar solo. Listening to the "Sweet

Sue" playback over Cooper's reading of lines like "I sing at the top

of my one good lung," Easter had a smile loaded with both mischief and

satisfaction. He's a reader, a huge fan of The New Yorker with books

piled up all over his restored 19th century house, but even someone who loves

the written word can grin at the way a musical instrument can steal the show.

Cooper, for his part, couldn't stop laughing, he was so happy at the way these

musicians had dressed up his words as few poets--anywhere, any time--have ever

been lucky enough to experience. This was taking the mood of his words, often

bleak and cryptic, and spinning something new and different out of it that still

feels like part of the original.

"It's not like there's a scale of darkness that just goes down from

black through brown through gray, but in musical terms, there are dark

places," said Frank. "Wherever this emanates from, it's someplace I

haven't been, but it's cool. I think people are going to listen to this album

and say, 'Wow, where was I?' Like they went to a movie or something. ... It's a

one-of-a-kind project, I think. There are some poetry albums, and some

songwriters who are more poetry slanted, but I think this is unique. It's a new

way of looking at poetry."

There's no telling what will come of the record when it hits stores in a few

months. Beal and Dixon can't even decide whether to stick with its working

title, Anything Goes--a good title, evoking not only Bell's novel, but

also the only bang-the-cow-bell-harder, mostly straight-ahead rocker on the

record, also called "Anything Goes." But a novelist-as-singer record

is bound to attract some attention.

Over the five days the tracks were laid down in the Easter studio, a sense of

elation steadily built. Maybe that's how it always goes when people make

records. I have no idea. This was my first recording session. But hanging around

as I did, more than 12 hours a day most of the time, I had a chance to see the

little, telling moments that give away private fears. What I saw was a lot of

talented, smart people who were just pleased as hell to be working together on a

project that was all about making something that sounded good to them, and maybe

to a few others.

"There's been such a focus on the commercial," Easter said.

"Everybody I know is dying for something with some substance. So here's

something with substance. A lot of people would love to hear it. Will the

mechanism be out there for them to get to it? I don't know. ... I think this

will do something. I really hope it does. That's what I'd like is just for it to

do something, to remind people that this sort of pop-music form is quite

adaptable and can be used to transmit some real information.

"Remember on The Beverly Hillbillies, they were making fun of

teenage rock music lyrics?" he said. "They had that 'Ooh Baby'

segment, which was really funny. Jethro has like a gold-lame suit and the song

went 'Ooh baby,' and that's all he says. When we go over to the little corporate

gym over here, and they have the hits station going, that's pretty much the song

they have going now. It's produced a little differently, but as far as I can

tell, they're quoting Jethro's lyrics pretty heavily.

"The 'Ooh baby' factor is like the only factor now in this incredible

way. I do think we'll look back on the late '90s and the early part of this

decade as an astonishing time for low-grade pop music. But it doesn't seem to be

satisfying anybody. So I think it's gone on like this long enough, and things

that are actually interesting have a chance again."

Limbering up

Bell, who runs the creative writing program at Goucher College, made his name

as a novelist writing hefty books like All Souls' Rising, a period piece

set in Haiti that was a finalist for the 1995 National Book Award. He likes to

take time out between long works of historical fiction (the new one has already

hit 1,000 pages, and it's not finished). That means limbering up, creatively and

otherwise, with shorter, more playful works.

"Anything Goes" started that way, and turned into something else.

Bell wanted to get Cooper writing fresh material, and asked him to write lyrics

to use in the novel, which they might later be able to sell, along with the

music Bell wrote for the songs. Cooper, a friend of Bell's since they were both

in the writing program at Hollins College 20 years ago, thinks the itch to make

music was stronger for Bell than the desire to add to his novel.

"His hidden agenda in all this was to set these songs to music,"

Cooper told me last summer. "He didn't really want the lyrics for the

novel. If he tells you that, he's lying. When I sent the first one, I got a

cassette back in about four days. He's set it to music already."

Soon they had a whole pile of songs, and weren't entirely sure what to do

with them. Some critics were distracted by the youthful narrator of Anything

Goes experimenting with songwriting--and having the lyrics appear as part of

the novel. (Bell and Cooper later cut a demo tape of the songs, which were

available to readers via Bell's Web site.)

I was given the novel to review for the San Francisco Chronicle last

summer, and having never met Bell or Cooper, I read it fresh--and thought it

worked beautifully. To me, it felt like a novel about being trapped inside a

box, and finding a way to knock loose a few holes and tunnel through to

something else. The sense of discovery was the point, it seemed to me, and came

through in what felt like an untold back story on where the songs in the book

came from. (I assumed at first that back in their school days, Bell and Cooper

had composed these songs and never found anything to do with them.)

Here's what I wrote for the Chronicle:

"About halfway through this deliciously entertaining novel about an

unexceptional blues and rock band and the series of dive bars it calls home, the

coked-up lead guitarist walks off in a huff just before a gig. This time, he's

gone for good.

"Desperate, the band turns to a squirrelly con-man character with

slicked-back hair and a 'fairly pleasant, hound-dog expression.' He's a loser,

the kind of guy who asks for a cigarette, pockets the pack, and then gives you

his best shit-eating grin when you ask to have them back. But he can play. The

dude can flat-out play.

"'A guy like that, he didn't have to play much to let you know what you

were dealing with,' the bass-player-narrator tells us. 'Five notes, one note, it

hardly mattered. Perry called this the authority, but I thought it was his time,

the rock-solid time tuning his hands to his head and letting anybody listening

know that this one did have the mojo.'

"That's the same feeling the reader gets early on about Madison Smartt

Bell in Anything Goes, his 13th book of fiction. Bell has the mojo, he

can flat-out play, and the tunefulness and life-knowledge and honest emotion all

come ringing off the page. The question, if you've got the mojo, is what to do

with it."

Bell, Shalini, Dixon

Later, following up as a reporter, I found out that Beal, a fan of Bell's

writing for years, actually wanted to make a record. Beal got the demo tape from

Bell, and sent it on to Dixon, best known for producing REM's first records,

along with Mitch Easter. Dixon right away agreed with Beal that the

music--featuring Bell on guitar--was intriguing. The only trouble was, they

didn't think much of the vocalists on most of the tracks. What they did like,

however, was the unbuffed, unpolished barfly voice on two of the tracks,

"On Eight Mile" and "40 Words for Fear." Bell was shy about

admitting that he was the one singing on those tracks.

"They said, 'We were listening to this and we wanted that guy who sang

those two songs--Can you get him?'" Bell remembered.

"I thought they were joking. I refused to answer that question for about

three rounds. And then I finally said, 'Yeah, I can get that guy.'"

Beal was surprised when he found out the truth.

"I told him, 'Well, you can't sing, but it's the WAY you can't sing

that's good,'" Beal said. "It has sort of a dark, sleazy feel to it.

They had about three or four people doing vocals on there, and this one voice

stood out. It was kind of a combination of Leonard Cohen and Tom Waits."

Catchy – and haunting

That was what Beal said in the summer. But those five days of jamming in

Easter's studio, just down the road from an auto repair shop and across the

street from a funeral home, showed the power of an idea: Dixon, the producer

with a glimpse of the barely possible, imagined something potentially enduring

in what others might dismiss. Bell had trouble seeing it, but he was willing to

go along with Dixon's vision. And Bell's singing became richer and darker and

more confident over the five days; some of the cuts are even catchy, or

haunting, which may be different sides of the same thing.

"We were lucky," Bell said late in the sessions. "I had no

idea what to expect coming in. I was nervous in a way. I sort of worked on my

head a little before I came down. I thought, I've got to tell myself that my

playing doesn't really matter and is dispensable and since I don't really think

of myself as a singer, I figure I can do that part and not choke. And that

worked.

"Never did I think this would happen. We were thinking maybe we'll get a

song here and a song there, established performers might pick this up. I just

truly thought when they started saying they wanted me to do it that it had to be

a joke. However, I was willing to try. I guess that's where you plug in that

line about I know you can't sing, but it's the way you can't sing that's good.

... There's something that Dixon is hearing in my inadequacies that works in his

idea of the music, and I'm getting detached enough from it now that I can hear

that, too."

That hang-dog expression Bell attributed to the guitar-for-hire in Anything

Goes might have some autobiography to it. Bell has one of those great faces,

part basset hound, part treasured teacher, that's the last one you'd single out

in a room full of people, but somehow also the first one you notice. He's

understated and low key without in any way undercutting his quiet authority. If

he was going to show up in a Hollywood movie, he'd be the new kind-hearted

teacher of the dark arts at Hogwarts Academy, teaching Harry and his mates

levitation or shape-shifting, all without an ounce of self-congratulation.

That first morning, coffee in hand to ward off the effects of the previous

night's eggnog, he good-naturedly cut off Dixon almost before he could get down

to talking about how he saw the music they were going to be making. "I

think a couple of these blues things are going to be OK, we just have to make

them kind of weird," Dixon said.

"I think this is the right time to mention that my timing really sucks,

and I can't count," Bell said. "It's kind of like a stutter."

Everyone laughed, and it was as if a background layer of anxiety or potential

vying of wills evaporated then and there and never came back. Bell was not

someone who was ever going to try to be something he's not, it was clear. Cooper

gets co-billing, and that's fair enough, but this was mostly about Bell and his

gifts. His timing--as promised--was nowhere near up to that of a professional

musician. That first day, realizing he had to play against a loop, funky and fun

in its syncopation, unforgivable in its regularity, he froze up a little, and

had to practice for quite a while before he felt comfortable. But he found a way

through that.

Not musical McNuggets

The worst thing about most contemporary pop songs is the icy loneliness of

hearing music that sounds devoid of an actual human presence. A singer like

Celine Dion can emote on cue without ever seeming to know much about what a real

emotion feels like. She's "feeling," oh baby she's

"feeling," count the Grammy, but it's emotion in the way that

McNuggets are food, stamped out of a mold, relentlessly and remorselessly.

Bell's voice does not have this problem.

"I hear somebody that means what they're

singing," said Jim Brock, the percussionist and co-producer. "I think

there's a lot of singers out there that could learn from that, a lot of really

great singers that could learn from that."

Brock talks in a low-key drawl and conserves his words so carefully, it seems

downright unfriendly to question what he says about others learning from Bell.

It sounds a little crazy, sure, but why not? Maybe all he means is that others

can learn something about trusting themselves.

"I think his delivery is completely effective," said Easter.

"There are a lot of ways to be a singer. It's the closer you get to Star

Search, the more you want to run for cover. That's not to say he can't

sing--he sings cool. He's not like a guy who would be in a cover band or

something, but he definitely has a real identity, and that's what you want. He

has that sort of well broken-in, been-around-the-block kind of sound in a way

that's very effective. He doesn't sound tired, but he sounds like a

grown-up."

What's also clear is that some people will be put off by that unlovely

quality in Bell's voice that gives it its honesty, and locates it for us as

listeners. It would be wrong to say that Dixon and the creative team behind this

record are unconcerned about people who actively dislike listening to someone

like Bell, singing in a way that could not be more different than, for example,

the airy world of Kenny G and that hapless guitar player in Animal House

who croons "I gave my love a cherry" and then watches a man in a toga

smash his guitar against a wall and mutter, "Sorry." In fact, these

people WANT strong reactions. That's the point.

"This is a recurring issue with me," Dixon explained one day during

the sessions. "Your enemies, the people who think you suck and are the

worst piece of shit ever to crawl out from under a rock, they define you more

than the people who just slavishly love you. They make the people who DO get you

have something to care about. If you can get some real hatred built up, then you

have a chance of defining yourself as a personality.

"It's the worst thing about popular culture, it tries to have too broad

an appeal. People want everyone to love them. I've seen totally talented but

incredibly insecure musicians worrying about some sack of shit person who

doesn't matter at all in their life, or ever will, and have them change

something totally good, because someone told them to do that.

"It's one's thing to get opinions from people you trust about something.

Not everything we crap out is good. We need filters. But it's another to allow

some idiotic comment from your accountant to change what you're trying to

accomplish. People thought REM was the biggest piece of shit, your typical sit

around a music store on Saturday and copy Joe Satriani, and thought they just

sucked. They didn't get it."

What will Don do?

The REM reference offers a hint that, like anyone putting themselves on the

line creatively, Dixon would love for a lot of people to love this record. Heavy

radio play would not be a bad thing, not for him, not for Bell and Cooper, not

for the other musicians--and, hell, not for the airwaves, either.

But as good as someone like Dixon has become at riffing with words in a good,

edgy, quotable way, there are always going to be discrepancies between the way

someone wants to be seen and the way they really are. Dixon might be the

smoothest, most people-friendly control freak around, a man with a genius for

relating to disparate personalities, each with just the right touch, but a

control freak is still a control freak. Or is he?

The test of the whole project came after that orgiastic third night of the

sessions, the night of the short-wave radio fuzz noise, and the banjo solo

coming in and out, and the big grins and the sense that real life just wasn't

supposed to be this fun. There was a creative buzz that night that changed

everything, added one more layer of depth and involvement to the music.

But how would Dixon respond? There was a heavy "Wait Till Your Father

Gets Home" vibe as the hours ticked away, and the producer's expected

return approached. Frank, always good for comic relief, tried to explain his

burst of nervous energy: "I'm just awaiting the arrival of the guy who

DIDN'T have a big steak dinner and a couple beers, and is going to be ready to

go."

Bell was especially eager to hear what Dixon would make of this wild, free

stuff. It was all part of Dixon's vision, clearly, and yet it wasn't. There was

a riddle here. Bell wanted to turn the page. He wanted to know what happened

next. But instead, Dixon cruised back into the studio, and a new song was begun,

with no time to waste listening to stuff already in the can. Like all the songs,

this took shape in a basic way, with Bell and Dixon and Frank and Brock sitting

around in the main studio, taking what Bell had written, musically, and building

on it, listening for more of it, exploring it.

But what about the weird stuff? The answer came the next day. Dixon had

gotten up early, and gone wild in the studio. He'd taken their freedom and

inspiration, and done them one better. As determined as he was to keep Cooper in

as an equal partner, he did his own reading of one of his poems, and strung it

together as a bridge between two songs. The room was dead-quiet as everyone

listened. Both Bell and Cooper were overcome.

"I was stunned," said Bell. "It brought tears to my eyes. Wyn

was serious when he said, 'Did I write that?'"

Later, Dixon would hedge on whether he was going to use his version of the

poem, rather than Cooper's. But everyone, including Cooper, loved his reading so

much, he's going to have to keep it and he knows it. It's just too good. If that

takes him a little time to accept, it's only fitting. Just as Bell and Cooper

came over from their territory, to play with these musicians in the best sense

of the word, so, too, the musicians were getting a taste of something different.

Dixon was reading poetry, and sounding great doing it.

This infusion of creative energy showed up most in Bell. The night Dixon came

back into the studio after the time away, Bell had some time to himself, and

picked up a guitar and started strumming. He had an itch to do something with an

idea kicking around in his head, and started putting chords together.

I found him that night out in the sofa of the front room to the studio,

strumming away happily, head down, lips pursed. He laughed shyly when he

admitted he was working on something new, but he was pleased, too. He liked what

he had. To my ear, it sounded less weird and dark than a lot of what had been

recorded during the session, but Bell told me no way, and I didn't press the

issue.

The next day, the song was added on to the record, as a short farewell called

"Wave Goodbye." The guitar has a rich, palpable sadness to it, a

mournfulness that is more lyrical than anything else on the record. But it's

beautiful. Hauntingly beautiful. And it works. Somehow it caps off this strange

effort, this odd collaboration of creative types lashing together something they

hope will float. "No man is an island shout the waves all around me,"

Bell begins, and by the end, he's saying "I wave hello, I wave

goodbye," and that's the end, sooner than we expect.

"It's like Madison said, it's the difference between throwing the

football around in the backyard, and all of a sudden you're in an NFL

game," Brock said. "If all of a sudden they sing something or play

something they like, they feel proud of themselves, and you see that grin. It's

cool. You don't want to lose that childlike attitude. But we all do, eventually."

photo by Abigail Seymour Photography no use without permission